GREEN KEY 2017

By: Betty Kim

By: Alexander Fredman

By: Debora Hyemin Han

By: Chloe Jennings

By: Jonathan Katzman

By: Amanda Zhou

By: Cristian Cano

By: Peter Charalambous

By: Ali Pattillo

By: Clara Chin

By: Julia Huebner

By: William Sandlund

By: The Dartmouth Editorial Board

Major: Undecided; Finding your academic path

By: Betty Kim

For many Dartmouth students, a drive to learn seems to come naturally; students are constantly engaged in a rigorous 10 week-term of three—or four— highly focused courses and several extracurricular activities.

However, once we try to trace back the intellectual motivation that fuels this constant “grind,” we might not always be sure why we do what we do. The phrase “I have no idea what I’m doing with my life” is surprisingly common among Dartmouth students — freshmen and seniors, students who have a top GPA and have a less-than-average one, students who have or don’t have any idea what they’re majoring in.

Both professors and students cited a liberal arts style education and an interdisciplinary approach as important factors in their learning, especially for students who were unsure which subject they wanted to pursue.

Dean of the Tuck School of Business Matthew Slaughter said he engaged in interdisciplinary learning during his undergraduate experience, specificially participating in a program called “Philosophy, Politics and Economics” as an economics major. According to Slaughter, interdisciplinary learning is important as it develops valuable life skills, beneficial to personal relationships and career skills.

“Especially for undergrads, some version of the liberal arts is so vital for their development as human beings,” Slaughter said. “[They learn] how to understand how they view the world from a philosophical or theological perspective, and what role each student envisions playing in the world to make it a better place.”

Even for students who are set on a particular academic track, Dartmouth’s promotion of interdisciplinary work and collaboration is an essential part of an undergraduate learning experience. Kevin Kang ’18, a Goldwater scholarship recipient who will be attending Thayer School of Engineering for graduate school, said he knew he wanted to do biomedical engineering on the pre-med track but was also interested in other STEM disciplines. Kang said Dartmouth’s academic plan provided the freedom to cultivate his diverse academic interests.

Similar to Kang, Brian Chung ’18 said he realized his sophomore year how grateful he was for Dartmouth’s flexible curriculum. Now an economics major on the pre-med track, Chung said he came to Dartmouth thinking he would major in biochemistry and go straight to medical school after receiving his undergraduate degree. However, his experience in the Great Issues Scholar Living Learning Community exposed him to different fields.

Chung said the flexibility to engage deeply in his peripheral academic interests has shaped his undergraduate experience; he attributed his decision to major in economics to Public Policy 26, “Health Policy & Clinical Practice,” which exposed him to healthcare policy.

His interest expands outside of his major as well. Chung said he has never regretted taking any non-major classes, and, even as a junior, is considering modifying his current major with computer science. He has also taken a senior level art history seminar and has a self-professed obsession with hours-long Wikipedia browsing sessions.

“Once you get out into the world your job will be your life; there are so few opportunities to learn or do anything outside your career, so I want to learn as much as I can before I dive into one career,” Kang said. “The best part [about life] is constantly enriching yourself as a person.”

Kang’s exploration of different interests is not uncommon. In a campus wide survey fielded by The Dartmouth from April 16 to 20, 428 students answered questions about changes in their intellectual and academic pursuits while at Dartmouth. 48 percent of students have kept the major they started off with while 53 percent of students said they either changed their major or did not have an intended major when they first came to Dartmouth.

Apoorva Dixit ’17, a Fulbright scholarship recipient who is majoring in anthropology and minoring in public policy, wants to apply anthropology to issues of public and global health to bridge the gap between western science and world cultures.

Even as a senior, she said she is keeping herself open to many different tracks. Alhough she is ultimately interested in working in global health policy, she said she is looking forward to doing many different things in the future, such as a research project, healthcare consulting, and potentially law school.

For her research next year, she will be going back to her hometown, Hodal, India. Through her college experience, she said she found a major and an opportunity to dig deeper about family and community that she comes from. In fact, she said she surprised herself upon rereading her Common Application college essay recently and seeing she wrote about wanting to go back to Hodal at such an early stage in her academic development.

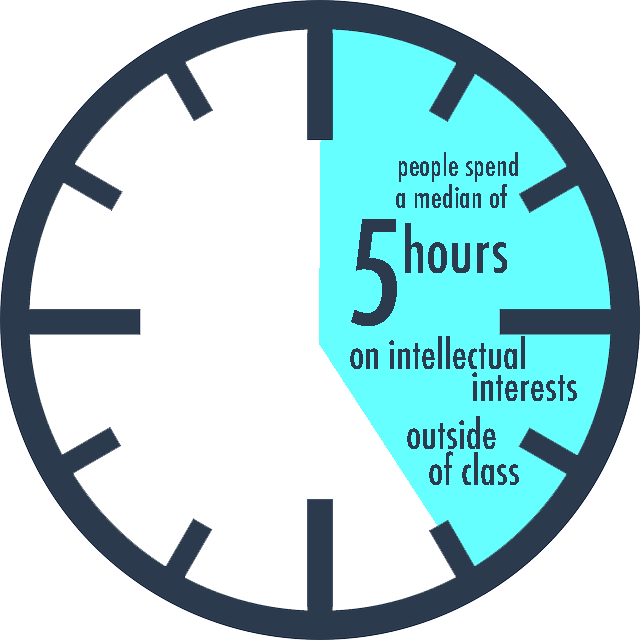

Similarly, many students at Dartmouth do not stop learning after they exit the classroom according to The Dartmouth survey; students devote an average of 6.28 hours per week to intellectual interests outside of the classroom. For Slaughter, students at the best schools do at least as much learning outside as they do inside the classroom.

“Classroom learning builds a foundation of knowledge and frameworks,” Slaughter said. “But college is only for a finite amount of time, so an ideal liberal arts education sets up people to be able to speak and learn for the rest of their life — interacting with people — empathizing — looking at other perspectives and processing that information.”

For others, outside sources of inspiration completely unaffiliated with one’s general field can help refresh and renew intellectual passion. Music professor Ashley Fure, who was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and awarded a Guggenheim fellowship, reported some stagnancy after entering graduate school directly after her undergraduate experience.

“I felt like everybody was myopic; writing music to get that next commission, it felt insular and not inspirational to me,” she said. “I was sickened by the culture and even reconsidered composing [as a] career.”

However, she said she realized soon that this was not the ultimate choice she wanted to make, and found a personal “intellectual renaissance” in other forms of art. Taking a brief break from being constantly immersed in music, she read Virginia Woolf and Susan Sontag and browsed the art of Robert Rauschenberg. Doing this fed her sense of direction and eventually allowed her to rekindle her desire to make music, she said.

Fure elaborated, acknowledging that burnout is real and should be respected. However, she also said part of ensuring constant intellectual development is learning to recuperate quickly, crediting her experience in art school as what taught her to not “wait around for inspiration to strike.”

“Sometimes you can’t muster that poetic insight, so you [take on] different aspects of the project, be it conceptual or expressive, pragmatic, or tactile,” Fure said. “As I’ve grown as a musician, all of those muscles have gotten stronger; so there’s this [same] thread of the desire to make the work, but my ability to execute it in greater and greater complexity has expanded since I was in undergraduate school.”

Fure also emphasized the dampening effect that anxieties about career choice may have on intellectual passion, saying that questions of what students are truly enthusiastic about can often get tangled up with questions of pragmatics. However, she also encouraged students to consider embracing that uncertainty and “taking the leap.”

These worries, however, do not appear to consume students’ intellectual interest, but seem instead to coexist with them. Only 1 percent of students reported that they took classes with only marketable skills and future financial success in mind. 20 percent reported they focused on both but more on practical skills, while 18 percent reported an equal focus, 50 percent both but more on intellectual interest and 11 percent only intellectual interest.

Interestingly, the percentages shifted towards intellectual interest when the classes had to do with a non-major class, with 59 percent of students reporting either only intelectual interest or more intellectual interest than easiness as their motivator for choosing non-major classes.

Regarding the pressures of career choice, Chung said that friends have reported feeling guilty about not knowing what kind of career they want after leaving Dartmouth, but encouraged students to continue exploring, as many people do not find their calling until they are in their middle years.

“Either you can get left behind or keep up with the flow in any kind of burnout; you might lose that drive at Dartmouth, but sometimes I just have to remind myself that I have to exert myself in order to get where I want to be,” he said.

He said that the most effective way students can awaken themselves academically is to take every opportunity to pursue their interests, citing a lecture series he attended about the moral limits of economics as a major influence in his academic life.

Slaughter also encouraged this kind of humanistic engagement to foster intellectual engagement. He pointed to the importance placed on information technology’s analysis of political behavior, rather than a much-needed focus on bringing together disparate voices and perspectives.

“There are subtle and not so subtle ways our culture and society values curiosity and asking questions and learning,” Slaughter said. “Advances in information technology are fabulous, but we’re not quite sure as a society what that does to foster empathy and constructive discourse.”

Like Chung, Dixit credited taking time to investigate something that catches one’s ear to expand one’s perspective, saying that the “random” classes or lectures she attended on a whim were often the most rewarding experiences.

Despite the various hurdles of academics and the fatiguing daily schedule of a college student, the continual search for academic awakening is a lifestyle for both professors and students of many different backgrounds. As Fure said, “Passion doesn’t look the same for everybody.” However, Dartmouth is a place that constantly fuels and energizes this endless search.

Coexist at Dartmouth

By: Alexander Fredman

At the beginning of her sophomore summer, Angelina Lionetta ’18 was worried about one of her upcoming classes. The course, a philosophy class called “Reproductive Ethics,” would cover subjects such as genetic enhancement, selective diminishment and abortion.

Lionetta is Catholic, and those issues, especially abortion, are sensitive among members of her religion.

Born into what she calls “an old Italian family” in Andover, Massachussetts, Lionetta grew up as an active member of her church: her parents took her to mass as a baby, she was an altar server and she taught Sunday School for third- through fifth-grade girls. At Dartmouth, Lionetta has continued to be passionate in her religious life, actively participating and organizing social events at Aquinas House, the Catholic student organization on campus.

Lionetta considers herself to be socially liberal, though she leans more conservative on certain issues. She said that as a woman and a pre-med student, she believes that abortion is a public health issue – one that has implications for both the mother and society. As a Catholic, however, she still maintains that life is sacred. For Lionetta, her beliefs on the subject can be challenging, as they differ from those held by some other devout Catholics.

Coming into her “Reproductive Ethics” class, Lionetta said she wondered how students in the class would react to her opinions – would they look down on her for her views? But after having conversations with the professor and engaging in small group discussions with fellow classmates, Lionetta said she realized her concerns were unfounded. In fact, she discovered that the views of her classmates were more diverse than she originally assumed.

Lionetta’s experience is not uncommon among religious students at Dartmouth. While students may face apprehension and misunderstanding of their beliefs, overt acts of prejudice are rare. Dartmouth students’ religious and spiritual experiences are understood best by the nuance used in describing individuals’ beliefs, rather than by attempting to generalize students into like-minded groups.

For some students, religion and spirituality does not play a prominent role in their Dartmouth experience. A recent poll of students conducted by The Dartmouth found that 43 percent of students identify as either atheist, agnostic or having no religion in particular, and 62 percent of students consider religion as either “not too important” or “not important at all.” But truly identifying an individual’s sense of spirituality involves more than asking those kinds of questions, Tucker Center dean and chaplain Rabbi Daveen Litwin said.

“I think what’s true about Dartmouth … is that while the language of religion is perhaps not, unfortunately, politically correct language these days, the questions that people ask [regarding identification of faith] are using a different kind of a framework,” said Litwin, giving the example that the word “religion” may mean an unquestionable belief in God for one person, but could simply mean a gathering place of family and community for another, she said.

Although religion as a practice may not be the central focus of academic institutions, Litwin believes that Dartmouth is rooted in religious and spiritual traditions. Dartmouth may not like to use the word “ritual,” she said, but it certainly has many rituals. And these rituals, while not ostensibly religious, often align closely with religious traditions, she said.

As an example, Litwin said, Green Key weekend may not on the surface seem like a religious event. Yet many religions have significant holidays during the spring to celebrate the awakenings of the season. Likewise, Litwin added, Green Key represents an opportunity for Dartmouth students to go outdoors and experience that renewal after enduring a cold, harsh winter.

At the Tucker Center, Litwin oversees 24 recognized religious groups on campus, which encompass all five of the world’s major religions. Tucker Center multi-faith advisor Leah Torrey estimates that usually half of the students who participate in such programs identify as atheist or agnostic.

“Often times people think of Tucker as a place for people who are religious, who meet some kind of litmus test around religious life,” Torrey said. “But it’s really students who are trying to better understand their own sense of ethics, their own sense of values, [and] their own sense of goodness in the world.”

One of those students is Emily Carter ’19. Raised in a non-denominational, evangelical Christian household in Washington state, Carter attended private Christian schools through middle school. When she reached high school, however, she said she realized that she did not feel the assurance of salvation that she had expected from her faith, nor did she find her emerging political views to be in line with her religious views.

“I ended up leaving religion because I realized ... it was something I was taught to [believe], not really because I had looked at it objectively and determined that that was what I thought I should [believe],” Carter said.

For Carter, coming to Dartmouth was an opportunity to explore her developing value system as an atheist and secular humanist, especially by taking philosophy classes and engaging in programs at the Tucker Center.

“At Dartmouth, it seems like people are more open to talking with and being friends with people who have beliefs that are different from theirs,” Carter said. “And that’s been sort of a good thing for me, to learn to be humble and accept other’s beliefs.”

Torrey said that college is an important time for students to develop their own value systems, especially since they no longer are influenced by their families and home communities on an everyday basis.

“Operating in an independent context takes strength, practice, thought, reflection and prayer,” Torrey said. An example of this concept in action is the Interfaith Floor, a living learning community sponsored by the Tucker Center, which brings students together from a diverse range of backgrounds.

Anirudh Udutha ‘18, who is the floor’s undergraduate advisor, said that residents write spiritual autobiographies describing their spiritual journeys at Dartmouth as well as participate in alternative worship services. He said that the benefits of these experiences include exposure to a diversity of thought and an open, communal atmosphere.

“Rather than having something in common ... your commonality is your interest in these questions,” Udutha said.

As an Indian-American who grew up in the Atlanta, Georgia area, Udutha knows what it is like to be a member of a religious and ethnic minority. At Dartmouth, Udutha has been an active member of the Hindu community, participating in the student group Shanti and helping plan major events such as the holidays Diwali and Holi.

For Udutha, being Hindu primarily involves the spiritual aspect of the faith, though he does participate in the ritualistic and cultural aspects as well. As a neuroscience major on a pre-med track, Udutha finds that Hinduism represents a way to tie his own sense of spirituality to his beliefs on social justice, community organizing and global health.

“Faith is usually tied to the concept of organized religion – like, a sense of God or something – and spirituality is a much more internal, personal thing,” Udutha said. “They’re connected, but not always the same.”

Udutha said that while Dartmouth has a significant amount of diversity – even within smaller groups like Shanti – people still tend to not be as aware of the customs and beliefs of others as they should. Although Udutha said he doesn’t find his spiritual beliefs to conflict with what he learns in the classroom, there are occasions in which people with whom he shares his identity as a Hindu have misconceptions about his faith and culture.

For Jacob Casale ’17, misconceptions about his faith have also been an issue he has faced at Dartmouth. As a former co-president of the Christian Union student group, Casale’s faith is a significant part of his life, both before and during his time at Dartmouth. Casale said that often acquaintances are at first not sure how to react when they find this out about him.

“When [my faith] is put on the table as the reality … people don’t necessarily really know what to do with that,” Casale said. “It’s just kind of like, ‘Oh, well that’s nice.’ And you kind of feel a little bit like an anthropological oddity.”

But Casale added that he sees this issue as a healthy challenge, and that meeting new people with different backgrounds and beliefs gives him the opportunity to constantly develop his own viewpoints.

Growing up in Seattle, Washington, Casale was raised by parents with Methodist upbringings, but never felt tied to one denomination of Christianity. He currently identifies as non-denominational Protestant, and believes that the specific sect of Christianity matter less than the individual’s personal relationship to God.

Casale said that being at Dartmouth has forced him to reckon with difficult questions regarding his faith such as the historical veracity and coherence of the Bible, as well as the intersection between faith and scientific reasoning.

“Christianity actually has a rich intellectual history, and has always welcomed intellectual engagement,” Casale said. “I think the Bible does hold together remarkably well.”

As a psychology major and geography minor, Casale admits that there are times when his beliefs do not perfectly align with the academic standard – for example, he believes that scientific processes and reasoning cannot answer some of the deeper, fundamental questions of life – but that this process of intellectual engagement with faith is beneficial.

“You can grow as a Christian in the classroom when your beliefs are kind of openly challenged – or even just in terms of thinking about what you’re studying in the lens of your faith,” Casale said.

Think Dartmouth: Work Hard, Play Hard

By: Chloe Jennings

Think Dartmouth: a school in a picturesque college town, charming but remote. A quintessential college campus, with a clock tower, a college green and a set of neatly matched, colonial-style academic buildings. Don’t forget frat row— throw in a hodgepodge of sorority and fraternity houses, a few American flags and a host of Greek letters to which students to pledge their allegiance. You have your setting.

Add a group of high-achieving individuals to the mix. Their academic experience is intense — a quarter system with 10 week terms, because who has time for syllabus week? The stakes are high, because they’ve worked hard to get into the school and they need to work even harder if they want that J.P. Morgan internship. But also remember that these students are social beings, so they’re not just occupied with studying. Think back to frat row. Students take a break from their econ finals, Spanish papers and history theses to blow off some steam on the weekends. There’s a deep reverence for the game of pong, an ongoing series of fraternity parties and a termly “big weekend.” With few off-campus social spaces, it is pretty much expected that one can step into a fraternity basement to check out what these students are up to — and to see whether the intensity of their partying matches the intensity of their study habits.

When you look at Dartmouth this way, it’s not surprising that the College is subject to stereotypes. Given the all-encompassing nature of Dartmouth — rigorous academics, a social scene that revolves around on campus Greek houses and a location that amplifies our commitment to both — it makes sense that the school has a reputation of having a “work hard, play hard” mentality. The fact that Dartmouth is both generalizable and unique, like a smaller, more intense version of a standard depiction of college, makes it an easy target for stereotypes.

Andrew Lohse’s’12 “Confessions of An Ivy League Frat Boy” paints a picture of the school as being little more than a playground for future Goldman executives — a place where preppy frat brothers ace econ midterms by day and morph into beer-guzzling animals by night and a place with Greek houses in which the future corporate leaders of America shake hands over games of pong and exchange stories of their sexual conquests. Dartmouth has been touted as epitomizing the downfalls of the Greek system and a nationwide epidemic of binge drinking and excessive partying. Add that to its Ivy League status, and you get denunciations of privilege and a condemnation of the “Dartmouth mentality” that keeps students studying hard and partying harder with little regard for the consequences of their actions.

To what extent are the stereotypes that surround life at Dartmouth true? I talked to a few students to gauge whether this “work hard, play hard” reputation is accurate, and to see how individual students might find balance in a culture where social and academic pressures can be high.

Isabel Taben’19 is an affiliated student athlete at Dartmouth — which means that she has to find time to balance lacrosse, clubs, her sorority and her social life.

“Sometimes, you have to sacrifice something, and lacrosse and school always come first,” Taben said. “But one of the things I like about being an athlete here is the flexibility that I have. Other schools pick classes for athletes, but I can major in whatever I want or even take a class when I have practice if I absolutely need to,”

People from other schools are often surprised to find that Taben is an athlete in a sorority, she said. However, she said that her time with her sorority is flexible and that students at a school like Dartmouth understand that everyone has other commitments.

Taben said that striking the right balance can be difficult and that it’s taken her most of her two years here to figure out how to effectively manage her time. For her, the fast-paced nature of the quarter system makes it particularly challenging to juggle athletics and academics.

“I’ve missed five days of classes for lacrosse,” said Taben. “When you only have 10 weeks in a term, if you miss a day, it’s a big deal.”

Despite her various commitments, Taben affirmed that she finds time to socialize on the weekends. According to Taben, this is typical of Dartmouth students.

“I would say that Dartmouth has a work-hard, play-hard attitude, to some extent,” Taben said. “But I think that’s a good thing, because people are really focused on getting their work done but they get a break to go out on the weekends with their friends and just have fun ... it’s hard to do work all the time if you never get a break from it.”

Sarah Kovan ’19 agreed that students do like to study and socialize but argued that the reputation is in part inaccurate.

“I don’t necessarily think that Dartmouth students actually party more than students at other schools,” Kovan said. “I think that Dartmouth has the reputation of being a party school because most of the partying that goes on is confined to the campus. At schools in less rural areas, students can go to bars and clubs in the city.”

Alternatively, Alex Chao ’20 explained that he was attracted to Dartmouth’s reputation when applying to college because, for him, it meant that Dartmouth provided academic and social opportunities.

“Students at Dartmouth deeply value their academic experience, but they equally embrace the opportunity to participate in a vibrant social life,” Chao said.

For Chao, balancing work and play means maximizing his productivity during free time.

“In my experience, balancing your social life and work means that you have to use the chunks of free time you do have efficiently,” Chao said.

I also spoke with sociology professor Janice McCabe, who studies the interaction between college friendships and academic success, to get a sense of what Dartmouth’s academic and social culture might look like from a sociological perspective.

McCabe recently published a book, “Connecting in College: How Friendship Networks Matter for Academic and Social Success,” in which she examined college students’ friendship networks. McCabe interviewed students at a large public Midwestern university, which she refers to as MU in her book. McCabe asked students to rate themselves on a scale from academic to social. Most of the students at MU rated themselves exactly in the middle (a score of 5), and three-quarters of the students rated themselves between 4 and 6. McCabe then compared these responses to the responses of Dartmouth students and found that the responses that she received from Dartmouth students were relatively similar to the responses she received from the MU students.

“If you just look at the average, the interviews I’ve been doing with Dartmouth students are quite similar, but there’s also more of a range,” McCabe said. “So the idea of balance seems to resonate really well with students here, but it seems like there are more students who see themselves as being more academic than typical. They feel like that’s a good balance for them.”

McCabe said that the academic rigor of Dartmouth may play a role in students’ ratings.

“I think when Dartmouth students are putting themselves in the middle, oftentimes academics is more objectively higher, but perhaps their social life is too,” McCabe said. “I hear a lot of that ‘work hard, play hard’ idea here.”

McCabe explained that, though students strive to balance their academic and social lives here at Dartmouth, few reported that their social lives were detrimental to their academic performance.

“There were times when students would tell me that their academics suffered because of social life, but it seems like those were more the exceptions,” McCabe said. “In general, people strategize to put academics first.”

It seems unrealistic to assume that Dartmouth’s culture varies drastically from its Ivy League counterparts or from other schools across the country. It’s easy to criticize Dartmouth, not only because the school is so classically “college,” but also because the extremely campus-focused nature of Dartmouth makes any issues that exist at Dartmouth particularly visible. However, Dartmouth students—like any college students— seem more focused on finding balance between work and play than pursuing extremes on either end. Of course, Dartmouth’s “work hard, play hard” reputation is not unfounded in that the College is a top academic institution with one of the highest levels of Greek affiliation in the country. In this way, the negative press that Dartmouth has received in recent years has been effective in drawing attention to issues that can accompany privilege, Greek life and an epidemic of binge drinking. However, while criticisms are valid and may indeed be amplified by the specific conditions at Dartmouth, they represent issues that exist across universities and Greek systems nationwide. They certainly should not be isolated to Dartmouth alone. It is also important to remember that Lohse’s portrait of Dartmouth — and the negative media attention that it sparked — caricaturizes Dartmouth students and ignores the diversity that exists within the student body. The portrait of the Dartmouth student as corporate-obsessed, diligent library goer by day and hard-partying frat brother by night is as dramatic as it is overly simplistic.

Kovan is a member of The Dartmouth business staff.

Coaches: On drawing the best out of their players

By: Jonathan Katzman

Legendary college basketball coach Bob Knight once said, “To be as good as it can be, a team has to buy into what you as the coach are doing. They have to feel you’re a part of them and they’re a part of you.”

While Knight’s message elaborates on the type of relationship required between players and coaches for teams to be successful, it does not imply that there is only one way to coach a team. Whether or not they have previously heard Knight’s statement, Dartmouth coaches across different sports have embraced the message’s sentiments.

Women’s tennis head coach Bob Dallis just completed his 15th season at the helm of the program. Dallis is also one of the more seasoned coaches within Dartmouth’s athletic department, with 29 years of experience as a Division I head coach and over 400 victories to his name. Since arriving in Hanover for the 2003 season, Dallis has coached his team to a share of two Ivy League titles -in 2011 and 2017- and overseen the development of numerous All-Ivy selections.

So what has been the secret to the women’s tennis team’s success during Dallis’ tenure as head coach? Dallis, who has a doctoral degree in developmental studies and counseling with a specialization in sport and exercise psychology, insists that he is still learning.

“Developing your coaching style is an ongoing thing,” Dallis said. “Certainly, I have always believed that working with a player’s strength is important. Because players work and understand concepts differently, you never master it. Every player you work with is different for a variety of reasons, and they all grasp concepts at different times.”

The strategy he uses to unlock his players’ potential however, is remarkably simple.

“Motivation is something that comes from within for each player,” Dallis noted. “Among the things I try to teach are love for your team, love for the game of tennis and love for Dartmouth.”

One of Dallis’ most successful players in recent years is Jacqueline Crawford ’17. This season’s co-captain and an All-Ivy selection, Crawford came to Dartmouth with a Women’s Tennis Association ranking of 800 and a plethora of experience playing at the highest levels of junior and adult competition. Dallis’ coaching is something that she credits not only toward her own development as a student-athlete but also to her maintanance of a strong team culture.

“I was lucky to have coaches traveling with me for most of my junior career, and they were entirely focused on tennis,” Crawford said. “Bob [Dallis] is not only a great tennis coach but also incredibly supportive in every aspect of our lives. He really emphasizes playing for each other and has allowed the players [to] shape the program’s culture.”

On the court, Crawford also noted that Dallis’ most significant contributions to her game have not been technical adjustments but rather embracing her team’s culture and strategy.

“When you play singles in college, it is very different from juniors,” Crawford said. “If you lose your individual match, the team can still win. Dallis has facilitated my development into a team player and also done a great job of individualizing what I need to work on. He encouraged me to focus on strategy and stressed that the differences in my performance would not come from strokes.”

Crawford’s collegiate tennis career has not only been shaped by her individual performances but also being a part of a team. Dallis, as well as assistant coach Dave Jones, have played a foundational role in both.

Dartmouth football associate head coach, special teams coordinator and secondary coach Sam McCorkle utilizes a different method than Dallis does. The son of a football coach, McCorkle caught the coaching bug following his undergraduate days at the University of Florida, where he served as special teams captain during his senior season. Following his 12th season with the Big Green, McCorkle’s name has become synonymous with energy and discipline within the football program.

“When we come in, Coach [McCorkle] tells us that he is not going to be our favorite guy over the next four years,” former Big Green safety and recent Jacksonville Jaguars identified free agent signee Charlie Miller’17 said. “He also tells us that he will make us great football players.”

McCorkle said his coaching style has a single goal: to make his guys better through perfecting technique. Having played under legendary head coach Steve Spurrier at Florida and as learning from now University of Oklahoma head coach Bob Stoops after beginning his coaching career with the Gators, he has had the opportunity to develop under the brightest minds in college football.

“I was raised and taught to make sure that everything you do is correct, and that football is a competitive game in which you never want to give opponents an advantage,” McCorkle said.

McCorkle noted that he tried to learn as much as he could from all of his coaches and gradually realized the techniques that fit him best on the sidelines.

“I have always been a high energy coach and paid attention to the details,” McCorkle said. “There is just no room for hesitation when you are on the field.”

At the same time, McCorkle recognizes that his players have different personalities. Making his players better also comes with wearing a doctor’s hat.

“You need to be a psychiatrist because personalities are different,” McCorkle said. “I know that, while some guys respond immediately after I get on them, others just don’t and it’s easy to lose them. Adaptability is also everything because some guys need more explanation than others, and it’s key to getting the most out of my guys.”

Miller was one such player who responded immediately. He switched to safety from cornerback during spring practice in his sophomore year, and credited McCorkle’s coaching as key to Miller’s eventual success at his new position.

“I was discouraged [about] being low on the depth chart at corner, but once I was moved to safety, I realized that I may have the chance to play right away,” Miller said. “Coach MacCorlkle had high expectations and critiqued everything that I did, but you come to respect that because it makes you better.”

Despite Miller’s success, he admits he had to adjust to McCorkle’s fiery demeanor.

“I am a pretty reserved player,” Miller said. “He would always try to fire me up when he saw that I was more internally inclined.”

McCorkle recalled that he believed Miller had all of the tools but was holding back athletically. He viewed holding Miller accountable for calling coverages and defenses at safety as instrumental to helping him build his confidence.

But what stood out most was the fact that Miller was always easy to work with.

“Charlie [Miller] was an easy one to coach because he was self-motivated,” McCorkle said. “I would have to get in front of other guys who would not hustle but never for him. He had all of the natural talent, and when I did have to raise my voice at him, it was only briefly because he would correct himself immediately.”

While McCorkle is loud and intense, he still insists that he is no different than other on-campus figures his players interact with daily.

“Just as professors set high standards for students, we challenge our players and set the bar high,” McCorkle said. “We aren’t in the business of holding your hand, but at time we will assist athletes who take has to take ownership and are willing to put in the work to reach their potential.”

Dallis and McCorkle may mentor their players differently, but in the end, they share the same goal. Their unique coaching styles prove that there is more than one way to awake their athletes’ potential and help them become the best they can be. After all, that is what matters most.

Phil Hanlon – Student, Teacher, College President

By: Amanda Zhou

When College President Phil Hanlon ’77 first arrived at the College in 1974, it was his first brush with what would become a life in academic learning and institutional improvement.

Hanlon grew up in a mining town in the Adirondacks in New York, a place so small it did not even have a movie theater. Although his hometown instilled within him a strong sense of community and valued hard work and the outdoors, it was not an academically-oriented environment, and arriving at the College exposed Hanlon to new perspectives.

For the first time, Hanlon met students from very different backgrounds, including students who had traveled to Europe and could name horses from the Kentucky Derby. Without any hesitation, Hanlon admits his transition to Dartmouth was “really, really rugged” and that he had struggled immensely with English 5, the then-equivalent of Writing 5.

“I had a very weak preparation academically,” he said. “I came here not knowing very much about the world, I would say.”

However, Hanlon views the College as a “transformative” place that taught him to “appreciate how much you can do with your intellect [and] with your mind.”

When Hanlon was a student at the College, there was a less developed “internal social scene” compared to the present. Prior to coeducation, road trips were especially common, as students often went off campus to find social life. The campus was far less diverse, with a population that was only 25 percent women — the rest were mostly “white guys,” he notes. His class was only the second class following the introduction of coeducation, a change he says most students favored, although alumni might have felt differently.

After graduating from Dartmouth summa cum laude, Hanlon found himself sick of winter weather and decided to go directly into a Ph.D. program for mathematics at the California Institute of Technology. The decision to go straight to graduate school stemmed from Hanlon’s experience with the math faculty at the College, who he said were always enthusiastic to share their research.

“What could be more fun than doing this?” he recalls thinking. “Than teaching really bright students [and involving] and doing research that you think is really cool?”

As an undergraduate, Hanlon had already completed three “solo publications” in combinatorics, enough work that he could have finished his Ph.D. in three years with a thesis. However, influenced by Dartmouth’s liberal arts philosophy of broad learning, Hanlon chose to write his thesis in number theory.

After completing his doctorate, Hanlon went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for his post-doctorate fellowship the school he had turned down four years earlier. There, he met his wife through one of his Alpha Delta fraternity brothers before obtaining a “really fancy [three-year] fellowship” at CalTech. But before he finished his first year, the University of Michigan contacted him and offered him the rare opportunity of a tenured position.

Hanlon describes his former professors and teachers with admiration, whether it was CalTech’s Olga Taussky-Todd, whom he credited as “one of the greatest algebraists of the 20th century” and a early women pioneer in mathematics, or former College President John Kemeny himself.

In Hanlon’s time, students regarded Kemeny with nearly a myth-like admiration. Everyone knew his story as the Hungarian teenage immigrant who came to the United States without any knowledge of English but still ranked first in his high school class. Along with Kemeny’s talent, students knew him to have been Albert Einstein’s assistant at Princeton University and worked with Richard Feynman on the Manhattan Project before he ultimately settled down as tenured professor at Dartmouth by the age of 27.

With Kemeny as his undergraduate probability professor, Hanlon recalls being simultaneously “blown away” and too shy to speak with him.

After around 16 years of professorship at Michigan, Hanlon was invited to become an associate dean, a job that he says allowed him to continue to be a student with constant learning.

After serving on a committee to select a new dean of arts and sciences, Hanlon was asked by the new incoming dean to become a vice-dean. Although he had not been looking to go into administrative work, the decision didn’t surprise him and almost seemed inevitable — he had served on various sub-committees and “spoken [his] mind” frequently.

Given the choice of working in any department, Hanlon as a longtime math professor with publications in advanced theory, elected to become the budget dean. At the time, he had never worked with budgets before, but he knew people paid attention to money.

Once his job began, Hanlon was no longer only paying attention to mathematics, he was thinking critically and learning about the operations of various departments. He describes helping departments as exciting and gratifying.

Three and half years later, Hanlon was prepared to return to his life as a faculty member, when the provost had another offer: the chance to manage the budget for the whole university. The University of Michigan was a large and complex place, but Hanlon saw the opportunity as a fun challenge.

Through the job, he was exposed to aspects of the university beyond the arts and sciences, and the job proved challenging when the university received a historic reduction in state appropriations. By the time Hanlon eventually became provost at Michigan, he says he was not originally seeking a college president position. But when he was contacted by Dartmouth, he could not resist the prospect of returning to work for his alma mater, a place that “did so much to change the direction of my life.”

While Dartmouth lacks the politically appointed governing board of a state university, Hanlon describes his position as especially challenging because of all the stakeholders. Faculty, staff, students, alumni, parents and the outside media all have different interests that need to be considered.

When Hanlon first arrived at the College, Dartmouth’s image as an institution was in chaos. Rolling Stone had published an article detailing the hazing rituals of a Dartmouth fraternity a few years prior. There had been a 14 percent drop in applications, which survey data revealed stemmed from a concern over the social scene. To add more fuel to the fire, Dartmouth was undergoing a federal investigation by the Office of Civil Rights, and the AAU Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct had also implicated the College.

The negative attention brought about such intense concern from the faculty that during the College president-led winter faculty meeting of the arts and sciences, the entire meeting was taken up by concerns over the College’s social scene.

With the campus “stirred up,” concerned trustees decided that action was needed to reduce harmful behavior, a goal that still drives their decision making today, Hanlon says.

When the original Moving Dartmouth Forward initiative announcement came out in 2015, it read, “If, in the next three to five years, the Greek system does not engage in meaningful and lasting reform, and we are unsuccessful in sharply curbing harmful behaviors, we will need to revisit the system’s continuation on our campus.”

When asked about the current state of this promise, Hanlon said that before making any final decision about the Greek system, he will have to consult multiple people. However, he adds, he is proud of the Greek system in its current state, as well as the reforms and student leaders within houses who have tried to make the spaces more inclusive and safe. The external advisory group turned a “very positive” report to the trustees, he says.

But on the recent topic that Alpha Delta will not be re-recognized, Hanlon says that, according to the student handbook, derecognition of Greek houses has always been permanent and that previous decisions to re-recognize houses were “unusual” and “exceptions.”

Hanlon said that a letter from the chair of the Board of Trustees Bill Helman ’80 sent on March 13 clarified that corporations currently owning the houses, such as Alpha Delta Corporation, may want “homes for new recognized student organizations” that are “substantially different in admissions and membership.”

“The trustee letter is intended to say that the exceptions that were made in the past really shouldn’t be made in the future,” he said.

Hanlon describes the MDF initiative as not only about social changes, but also academic. As examples, he mentioned the construction of an “arts district” that will eventually become a part of the creative mind initiative to develop students creativity mind, as well as the recent creation of the Arthur L. Irving Institute for Energy and Society. As a former student, Hanlon says his experiences at Dartmouth have informed his view of what the “heart and soul” of the College is, although he also brings his perspectives of scholar, teacher and parent to his role.

Although most things are in early stages, Hanlon expresses optimism about the future and ongoing conversations.

“You may have noticed … that not all our [housing] is in great shape,” he said in half-sarcasm.

In addition to renovating the Choates, the River Cluster and the Lodge in the next few years, he says the administration hopes to develop a kind of “village” in College Park near BEMA. Whether that development would be to accommodate a 10 to 25 percent increase in the student body, or simply add options, is still an ongoing conversation.

For Hanlon, the College is where he found his academic passions as a college student and the place where he began the final stretch of his administrative career. Carrying a respect for broad learning, he left the Granite State on a whirlwind of academic programs and fellowships which would ultimately lead him to become a professor. His transition to administrator was natural, another way to pursue learning and improvement, and would ultimately lead him back to Dartmouth, ready to begin again.

20 Things 20s Learned

By: Cristian Cano

Freshman year is a time for many adventures, but above all, it is a time of learning.

For some students, living at college is the first time they’ll be away from home. For others, attending college feels more like home than anything they have ever known before. But for everyone, college is where many lessons are learned. Hopefully, many of those lessons are academic — but the other lessons, of a more personal variety, are just as important.

As spring term comes to an end, The Dartmouth spoke to members of the Class of 2020, asking them what have been some of the most important lessons they’ve learned since arriving at the College. These lessons touch upon different experiences, but they all reflect the many ways in which students grow during their first year.

Arriving On Campus:

- “I brought way too much stuff. I brought a dozen pairs of shoes and way too many jackets that I only wear a few of, so now it’s a very cluttered room for no reason. I guess it just extends to being over prepared in general.” Nicholas Windham ’20

- “How to live with a roommate in the same room. This is my first time living with another guy in the same room. We each have different schedules and lifestyles. I could never imagine living with a guy like this in my high school years. After a year, I feel like even though we have different schedules, things are likely to work out most of the time.” Timothy Qiu ’20

- “Try to make friends with upperclassmen. They’re not as intimidating as they seem.” Samuel Greenberg ’20

Chances are, you were welcomed to campus by a mob of upperclassmen wearing outrageous clothing that you soon learned was called flair. Many freshmen embark on First-Year Trips before they truly settle into their dorm room — after five days with no showering and minimal access to toilets, even the worst of Dartmouth’s dorms seem luxurious. Even if you didn’t go on a Trip, though, move-in day is a blur of carrying boxes up never ending flights of stairs, meeting people, immediately forgetting their names and asking yourself if you brought too much or not enough stuff. (If you have to ask, the answer is probably yes, you brought too much.) Thankfully, there’s nearly always a Crooling or O-Team member around once you finally swallow your pride and decide to ask for help.

Orientation week:

- “I’ve learned the importance of finessing the Collis stir fry line. Like college, the stir fry line can be very intimidating and stressful, but over time and with the help of some friendly people, I’ve really learned how to get what I want out of Collis.” Emma Demers ’20

- “Tenderbob with added hash brown. Prime.” Dylan Giles ’20

- “‘FOMO’ is a thing, but don’t give into it. For every one thing you choose to do on campus, there are a hundred things you want to do but don’t have time to do. I think it’s important that you have to make so many decisions about what’s the best use of your time and what’s most valuable to you, because forcing yourself to make those choices will give you a chance to hone in on your interests and passions.” Jessica Kobsa ’20

Life at Dartmouth takes some time to get used to, and even something seemingly as simple as ordering food at Collis or the Hop isn’t always straightforward. Thankfully, Orientation week gives students the chance to gradually acclimate themselves to their new home. In addition to the many required meetings, panels and information sessions that freshmen attend, there are also the many social events that introduce students to one of the most important aspects of college life: free food. There are so many activities that not even the most eager of freshmen can attend all of them — but thankfully, you don’t need to make any commitments just yet. So take it easy, explore whatever sounds interesting and remember that there is never any shame in dedicating time to take care of yourself, especially while transitioning to college.

Classes and Clubs:

- “I learned how to enjoy myself. In high school, I didn’t do that, but here I find that I have a lot more free time to do things that I enjoy doing, like making memes.” Jeffrey Qiao ’20

- “It never pays off to fall behind in your classes and then try to catch up.” Nia Gooding ’20

- “I discovered a lot of people that share many of my passions here, so I feel that it encouraged me to do better in school, study more and participate in activities. I felt that before, I wasn’t in an environment that encouraged that, so it’s been great to find people whom I feel I can share my passions with.” Pedro Salazar ’20

During orientation week, it is far too easy to forget that the primary purpose of college is to receive an education. Once the first day of classes arrives, however, that becomes more and more difficult to forget as your workload steadily increases. Classes at Dartmouth jump right into the course material thanks to the quarter system, which means that there is no such thing as a syllabus week. After a few weeks, however, students will get a sense of the pace of the academic schedule, while figuring out how to dedicate time to other interests. You might be the person who signed up for way too many clubs at the club fair or the person who didn’t sign up for any; regardless, you can certainly check out both pre-existing and new interests. Again, no pressure: You can always drop out of a club or join another one later!

Discouragement and Motivation:

- “The presence of someone else’s _______ is not the absence of your own. Fill in the blank however you want.” Lola Adewuya ’20

- “I’ve learned that it’s okay to struggle and to fail sometimes. I’ve also learned that, while grades define your academic success at Dartmouth, your friends define the person that you are.” Samuel Hernandez ’20

- 12.“I’ve learned that it’s tough being in an Ivy League institution because when you come from a place where you’re considered the top, and then you’re suddenly not the top, it’s tough accepting that.” Jean Fang ’20

- “What I’ve learned over freshman year: even if you receive a midterm back and it doesn’t go as well as you’d hope, going to office hours can be very beneficial. Professors can be very helpful: they don’t want you to fail, they want you to succeed. They’re all very supportive.” Meghan Poth ’20

College is hard. The 10-week term moves quickly, and it seems like everyone else already knows the material even in the introductory level courses. Some groups are competitive to get into, and after a cappella auditions don’t go so well, you might feel like never singing again. Even if you excelled academically in high school, you might get a less-than-stellar grade on your first midterms. You’ve heard again and again that it’s normal to struggle, yet it’s still so hard to accept that it’s normal for you. But as you begin to doubt your abilities and wonder if you made the right choice in coming to Dartmouth, you can also discover the importance of support systems. Whether your own support system comes from friends, family, professors, advisors, deans or a combination thereof, never forget that there are so many people, on campus and beyond, that genuinely want to help you succeed however they can.

Developing Priorities:

- “I have learned the importance of taking time to do things other than homework and to do things that are fun sometimes.” Alexandrea Gosnell ’20

- “A day that’s no fun is a day without a pun. I’ve really connected with people by making sure I say something nice about each person I see every day. That’s either giving a genuine compliment or telling a funny joke.” Sirey Zhang ’20

- “I would say that there are some experiences that are worth pulling an all-nighter for. Like, ‘Hey, let’s go to the golf course at midnight. I have a bunch of work to do, but yeah, let’s go do that.’ You know, just hanging out and thinking about life.” Gregory Szypko ’20

The sheer number of things to do on campus at any given moment is pretty overwhelming. There are performances to see, guest lectures to attend, games to play, books to read, research to do ... the list goes on. Once the frat ban is over, an entirely new option for socializing is available for ’20s to enjoy — or ignore — as much as they want. With all of these options, many first-years realize that they need to evaluate their priorities and adjust their schedules appropriately. That might entail quitting a club or two or limiting how often they go out. That adjustment could also be much more drastic, like spending less time with certain groups of people or changing academic interests. Such decisions differ from person to person because each person’s priorities are different. With the power to plan their own schedules, first-years learn from experience exactly what they want out of college and out of life.

Life Lessons:

- “I don’t owe anything to the me I was yesterday.” Mary Clemens-Sewall ’20

- “One thing I’ve learned over this year is that people cannot be put into boxes of good and bad. People are much more nuanced than that. Meeting so many different people coming from different backgrounds and talking to people with different beliefs to me has made me realize that that is simply not the case” Naman Goyal ’20

- “When people say that everyone’s experience is different than everyone else’s, it actually means something. It’s not just a cliché people say. Everyone comes from their own place, everyone has their own way of doing something, and that’s fine.” Arunav Jain ’20

Often, the most profound lessons are not taught explicitly but instead are slowly learned through a continual process of experience and reflection. There is no one way to experience freshman year at Dartmouth, and to that end, there is no single lesson that all freshmen must learn — nor should there be. Over the past year, each ’20 has learned many lessons: some funny, some lighthearted, all important.

I offer one final lesson, in my own words, that I have learned during my own freshman year. Being a first-year isn’t always easy, but the lessons I’ve learned have improved my life more than I could have ever imagined. I hope this one improves yours as well.

- “No matter who you were when you arrived at Dartmouth, and no matter who you are now, you deserve to be here. Don’t forget that.”

Demers is a member of The Dartmouth Staff. Jain is former member of The Dartmouth Staff.

The New Story of Dartmouth

By: Peter Charalambous

This is the new story of Dartmouth. It is written between night shifts at Novack and pong games on Webster Avenue, between the time spent stressing about academics and the countless hours worrying about relationships, between the final hole of the Hanover Country Club and a seat in the financial aid office. Its authors, the most socially and economically diverse class of students in Dartmouth’s history, come from different backgrounds and bring varying perspectives on issues from campus life to politics.

It’s a story about changed perceptions, the difference between what Dartmouth was expected to be and what it actually is. It’s a story shaped by both social interactions and socioeconomic class, and it’s a story that is constantly being rewritten.

Decades ago, the story of Dartmouth students would be predominantly homogeneous. In 1972, the first year of co-curricular education at the College, nearly 90 percent of students at Dartmouth were white, and nearly the same percent of students were male. Today, the student body is comprised of a nearly-equal split of males and females. While a plurality of students are Caucasian at Dartmouth, Asian-American, African American, Latino, Native-American and multi-racial students comprise a large percentage of the student body.

Social diversity shapes campus life at Dartmouth — yet another factor, economic class, also plays a major part in overall campus life. Nearly 70 percent of Dartmouth students come from families that make over $110,000 annually, landing the majority of the student body in the top-20 economic percentile in the United States. Twenty-one percent of students at Dartmouth come from families in the top 1 percent, while less than 3 percent of the student body come from the bottom 20 percent.

These two factors have contributed to a growing socioeconomic divide on campus. In a campus-wide survey conducted by The Dartmouth from April 16 to April 20, nearly 81 percent of students said that they perceived a social economic divide on campus, and 71 percent said that their perception of socioeconomic class has changed since coming to Dartmouth. Attesting to the effect of socioeconomic class, 79 percent said that economic factors shape relationships on campus.

In the following interviews, names have been changed because of privacy concerns and the sensitive nature of topics.

Anthony is a first-year student at the College who grew up in a low-income single-parent household in Maryland and attended a low-resourced school. For him, Dartmouth was expected to be somewhat of a culture shock.

“I thought it was going to be white and preppy, and I was going to have a lot of white friends,” he said.

Leaving his family and the diversity of his hometown, he was worried that he might lose his identity. This perception of Dartmouth, while not entirely false, proved different when he arrived in Hanover.

Anthony lived in Thriving through Transitions (T3), a Living Learning Community, which connected him to a community of students who also came from similar backgrounds. Many students from this floor come from predominantly low-income households and are often the first members of their family to attend college. He was also able to connect with his African-American identity through the College’s Afro-American Society. While Hanover was not as diverse as his hometown, his original perception of Dartmouth was not quite accurate.

“I have come to love the Dartmouth community for its enriching aspects a well as its negatives,” he said. “You know you’ll have someone to stand next to.”

Anthony’s perception of Dartmouth is not unique, as many students come to Dartmouth and find that many of stereotypes associated with the College do not represent the student body.

“There are so many people,” said Erica, an international student. “[The white and preppy] stereotype does not define the entire campus.”

She noted that the overall diversity of the campus has made her experience more welcoming than she originally expected.

While some are surprised by Dartmouth’s social offerings, other students, however, do not find the College to be as diverse as they originally expected.

“It was way worse than I expected,” said Josh, a first-year student from a low-income background.

Growing up in an extremely diverse public school district in Los Angeles, Josh was exposed to different ethnic and socioeconomic groups. In regard to finding diversity on campus, Josh said coming to Dartmouth was a sharp turn in the wrong direction.

Not only was Dartmouth’s social diversity an issue, Josh said, but the divisions caused by economic status also became apparent. When students mentioned the extravagant family trips during class discussion, Josh said he felt discouraged and isolated, as he could not offer similar input given his socioeconomic status. When he attempted to create a dialogue across socioeconomic lines about identity, he said he also realized that overall student apathy regarding socioeconomic issues prevented meaningful discussion.

“To have a community, you need different voices,” he said.

Despite these challenges, Josh has been able to find a meaningful community on campus through different organizations. For him, these organizations provide a connection to his heritage and community in Los Angeles.

Each student on campus has a different story about how their identity has changed since arriving to Dartmouth. For some students, that story is harder to tell than others. Ultimately, true empathy rather than apathy is needed to keep that conversation alive, Josh said.

One of the largest problems for low-income students on campus is what director of Dartmouth’s First Year Student Enrichment Program Jay Davis ’90 said he likes to call “small money.” “Small money” is the cost of the minor things that appear throughout a term at Dartmouth. While Dartmouth may cover the full costs of tuition and board, these small costs escape the hands of McNutt Hall. From the $50 late check-in fee at the beginning of the term to an end-of-the-term meal to celebrate the conclusion of finals, these costs can be major burdens for Dartmouth students who come from low-income backgrounds. Furthermore, many students do not expect these costs at first, Davis said.

When Amanda, a first-year student from a low-income background, forgot to check-in during the first term, she encountered a $50 late fee. While this cost may be a minor issue for some, it was a major burden for Amanda, she said.

“My family needs that money ... the costs begin to add up,” she said.

This small cost was the first of many that Amanda said she encountered over her first year. From an invitation to have a meal at Lou’s to the desire to spend a day at the Dartmouth Skiway, these costs prevent some students from spending time with friends and enjoying the full “Dartmouth experience.”

Furthermore, James, a first-year student from Long Island, New York, said, saying that no to an invitation because of financial reasons does not always have an easy solution. Some students, unwilling to open up about their own financial situation to new friends, use an excuse unrelated to finances when they decline an invitation. Instead of explaining financial limitations, they give the impression that they would not like to get a meal with the person who offered the invitation. Other times, they might be the only person in their friend group not able to go out on a trip.

“I work jobs on campus to avoid those kinds of situations,” Josh said.

When the College decided to no longer make financial aid need-blind for international students, Chris, a self-identified low-income international student from England, was forced to wrestle with questions of belonging and inclusion.

“Money has always been like a storm cloud over my family,” he said.

With his family abroad still struggling with money problems, he said he worries both about his academics and his family life. At times, these worries become difficult to handle.

“I was wrestling between two black holes of attention … the more [work] I throw myself [into], the more I distance myself from my family,” Chris said.

While Chris has found comfort in his friend group on campus, the question of his place at Dartmouth still follows him throughout the term. The question is not unique to him.

This year, more than 70 percent of regular-decision prospective students who attended Dimensions decided to come to Dartmouth. While they visited, they were able to see and interact with some of the best parts of Dartmouth: welcoming organizations on campus, a better-than-usual set of meals at the Class of 1953 Commons, a beautiful campus and, most importantly, Dartmouth’s enthusiastic and welcoming student body, said Tim, a student from New York. For a majority of students, Dimensions provided one of their first interactions with the College, an experience that will likely shape their initial perception of the school.

However, many students’ original perceptions of the College do not match the reality. Tim said that while the experience of Dimensions was a great introduction, many of its aspects are hyperbolic in that Dimensions highlights the positives of Dartmouth and ignores the negatives.

“I bought into the way they sold campus,” Tim said.

He noted that Dimensions does not take enough time to talk about the negative aspects of Dartmouth. Instead, students have to learn about those aspects when they come to campus in the fall, which makes the transition into college even more challenging.

“We should just be honest with people,” said Erica.

Dartmouth has divisions. Few can deny that. These divisions are visible in everything from campus jobs to student organizations. Those divisions are positive though. Because of these divisions, however, we are reminded of this institution’s scars which have not yet healed. We derive strength to work together and resolve issues so that regardless of race, gender, economic status or any other factor, students feel loved and at home on its campus. We are united in that pursuit. Dartmouth may have its divisions, but Dartmouth is not divided.

A Cure for Phantom Pain

By: Ali Pattillo

It’s 5:30 p.m. on an especially warm spring night. Sunlight’s last rays cast across Mink Brook. There’s a Bernese mountain dog playing fetch with his owner, periodically running head first into the water and shaking his fur across the sandy bank. her students have strung up their orange and purple hammocks on two nearby trees and have spent the past hour pondering both our sense of mortality and the best way to make a Collis breakfast sandwich. I’ve just finished a long run through the winding trails that lead to this sun-soaked corner of the Upper Valley. Lungs pounding from the end of my run and sweat pouring over my face, I strip down to my shorts and sports bra and dive into the brook. The shockingly cold feeling is immediate and visceral as my body adjusts to the temperature of the river. I lean my head back and float, feeling the warmth of the first few inches of the water. I see tiny birds darting in and out of clouds ahead. I feel some river weeds wind around my legs. I am buoyant, free from my commitments and suspended from stress.

I am living in a dream. It’s a dream I come back to, time and time again. I dreamt of it on my foreign study program in Prague and while sitting in my living room in Atlanta on my off-term. It’s the dream I’ll carry with me long after I leave this college. I’ll carry other dreams of hiking through blazing red leaves in the fall, making homemade pizza at the Dartmouth Organic Farm, dancing on elevated surfaces in basements or taking midnight walks to the golf course. I’ll dream of the days I pushed away my work and responsibilities and instead took a drive or walk with friends to paint pottery, visit a farm or go to a diner to eat oversized blueberry muffins. I won’t dream of the endless nights I spent pouring over papers, the hours and hours I spent in the periodicals on sunny days or the time I skipped lunch with a friend to print photographs in the darkroom.

No, Dartmouth hasn’t always felt like a dream. At times, it’s been incredibly difficult — even nightmarish. At Dartmouth, we rarely talk about the issues we carry, the things which inform our perspectives on the world or hurt us and shape how we treat others and view ourselves. Every student, every human being, carries with them a kind of phantom pain.

Phantom limb syndrome means feeling something that is no longer there and feeling something that you cannot see. When a limb is amputated, the pain doesn’t always stop; the feeling of that limb, how it moves, its weight, doesn’t just disappear. After it’s gone, you can endure unexpected pain with no known cause for months, even years. Phantom pain, similar to phantom limb syndrome, is feeling a gnawing sense of longing, deep in your bones.

For some of us, it’s the depression we hide from our roommates, the drug habit we just can’t kick, the feeling of exclusion on this overwhelmingly white, wealthy campus, the parent at home who depends on us a bit too much or the crippling sense of self-doubt that we feel might swallow us whole.

My phantom pain is panic. I spent much of my freshman spring term dealing with panic attacks which made my breathing go shallow and paralyzed my body and mind. Growing up and throughout high school, I never felt like the world was closing in on me, until that freshman spring.

Like many other Dartmouth students, I don’t often let others see my phantom pain. I exude positivity, even on days when it isn’t authentic. Sharing what we carry or showing our weakness would make us soft — and we are not soft. We are badasses. We are environmental engineers and early-admitted medical school students and Fulbright scholars. We bury this phantom pain over and over, beneath accomplishments and successes.

How do we alleviate the phantom pain, externally invisible yet omnipresent in our lives?

The only antidote I’ve found is to pay attention to the moment.

At dinner the other night, a very wise friend shared a quote by the poet, May Sarton: “The quality of life is in proportion, always, to the capacity for delight. The capacity for delight is the gift of paying attention.”

When the future is too daunting to imagine and the past too painful to remember, engage in the present.

I would not have survived at Dartmouth without this strategy. By actively practicing it, I’ve been able to consistently quell this panic and develop real happiness.

This act of paying attention is what I grab onto when the water rises above my head. Any time panic rises within me like a rustling wildfire, I actively feel the air in my lungs, look up to the sky to explore the curling wisp of a cloud or look down and notice the slight bend of a blade of grass reaching toward the sun. I listen intently to friends, ignoring my phone or my desire to think of my seemingly endless to-do list. I try to lessen their phantom pain and in doing so, alleviate my own. I remind myself that I have a heart that pumps 83 gallons of blood through my body every hour and a brain with neurons that fire 200 times per second. I am alive. I shift my focus back to the present, I exhale and my phantom pain slowly fades.

We’ve all had moments that change the course of our lives forever, moments which shake us out of normalcy. Maybe it was making a mistake and hurting a person you loved or failing a final exam after a late night out. Or maybe it will be saying goodbye to Dartmouth. Maybe it was the first time you experienced loss or grief or suffering or deep hurt. Maybe it was when you watched classmates lose their chance to be in this world.

These moments remind us that there are no guarantees. We are not promised anything in life. We are not promised the chance to graduate or start our careers or get married or grow old. We are only promised the moment at hand.

Do not be afraid of what might be lost. It will be lost. Ultimately, the only relationship we will always have is with ourselves. Everyone we know will eventually die or move away or have six children and no time for weekend ski trips or weeknight drinks. But do not agonize over this reality that you stop living the only life you have. Don’t attempt to climb the slippery slope of prediction or prevention of these realities to the point that you lose sight of the beauty and the people in front of you.

Instead, dive headfirst into the universe a moment can hold. Be astonished.

This is how you cure your phantom pain, if only for a moment.

I’m back at Mink Brook. I’m floating in the lazy current of the shallow water. I’m disconnected from the world around me, calm and content. I swim back toward the shore, begin to make my way up the bank, sand soft on my feet. I’m walking in that familiar dream. I’ll wake up soon, but for now, I’ll savor the last few ray of sunlight, warm on my skin.

Pillow Talk: What's unspoken about sex at Dartmouth

By: Debora Hyemin Han

Many students have become blasé to the “hookup culture” on college campuses. For Dartmouth, the phrase falls into the same categories of “Greek life” and “drinking culture”—things students don’t seem to question after a couple weeks on campus. What fails to follow this normalization of the casual hookup is an open conversation regarding various aspects of sexual health and wellbeing.

The Center for Disease Control reported that 2015 saw yet another increase in reports for all three nationally reported sexually transmitted infections — chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis. Reports for chlamydia, which amounted to approximately 1.5 million cases nationally, were at the “highest number of annual cases of any condition ever reported to CDC.” While the 15-24 age group makes up about one quarter of the sexually active population, it also accounts for nearly half of the 20 million new sexually transmitted infections that occur in the United States each year.

Given these statistics, it seems logical that high levels of sexual activity will increase the probability for exposure to and spreading of STIs. However, students don’t seem to be as markedly concerned about STIs before they have sex, as much as these numbers might suggest. According to a campus-wide survey conducted by The Dartmouth from April 16 to April 20, 63 percent of students said that sexually transmitted diseases and STIs are things they worry about when they are sexually active. However, whether these worries will affect their willingness to have sexual encounters was less clear. Forty-eight percent of students either strongly or somewhat agree that concern about STDs and STIs affect their willingness to have sexual encounters, while 36 percent strongly or somewhat disagreed.

Cindy Pierce, local author and self-described social sexuality educator, said that she was surprised at the lack of knowledge college students overall have about these issues, especially in light of the Internet and the access to information it provides. She said that young adults today are “even more off track” than her generation was when they were growing up in the 1980s, a time that she described as “repressed” and “conservative.”

Karina Korsh ’19 also disputed whether the narrative of progress in gender equality is as powerful as people have been led to think. She said that while people may think feminism has gained traction and “new notions” of female sexuality are more widely accepted, there are still aspects of society that have yet to fully embrace the progression.

“When we have these sexual norms that are around for so long, discussion with society about feminism can help spark change but it’s not enough, and no change is going to appear this quickly unless we talk about sexuality,” she said.

According to Cindy Pierce, the freedom to hook up seems to be a form of feminism, when in reality, it reinforces male-dominant relationship dynamics which often prioritize male satisfaction.