By: Alexa Green

House Center A hosts social events for North Park and South Houses.

Last winter, Dartmouth introduced a new residential life model as part of College President Phil Hanlon’s “Moving Dartmouth Forward” initiative. The College’s stated purpose in creating these six new housing communities is to foster more opportunities for intellectual engagement through social encounters among students, faculty and staff. House professors, undergraduate advisors, graduate student fellows, student leadership teams and affiliated faculty are all involved in the Houses.

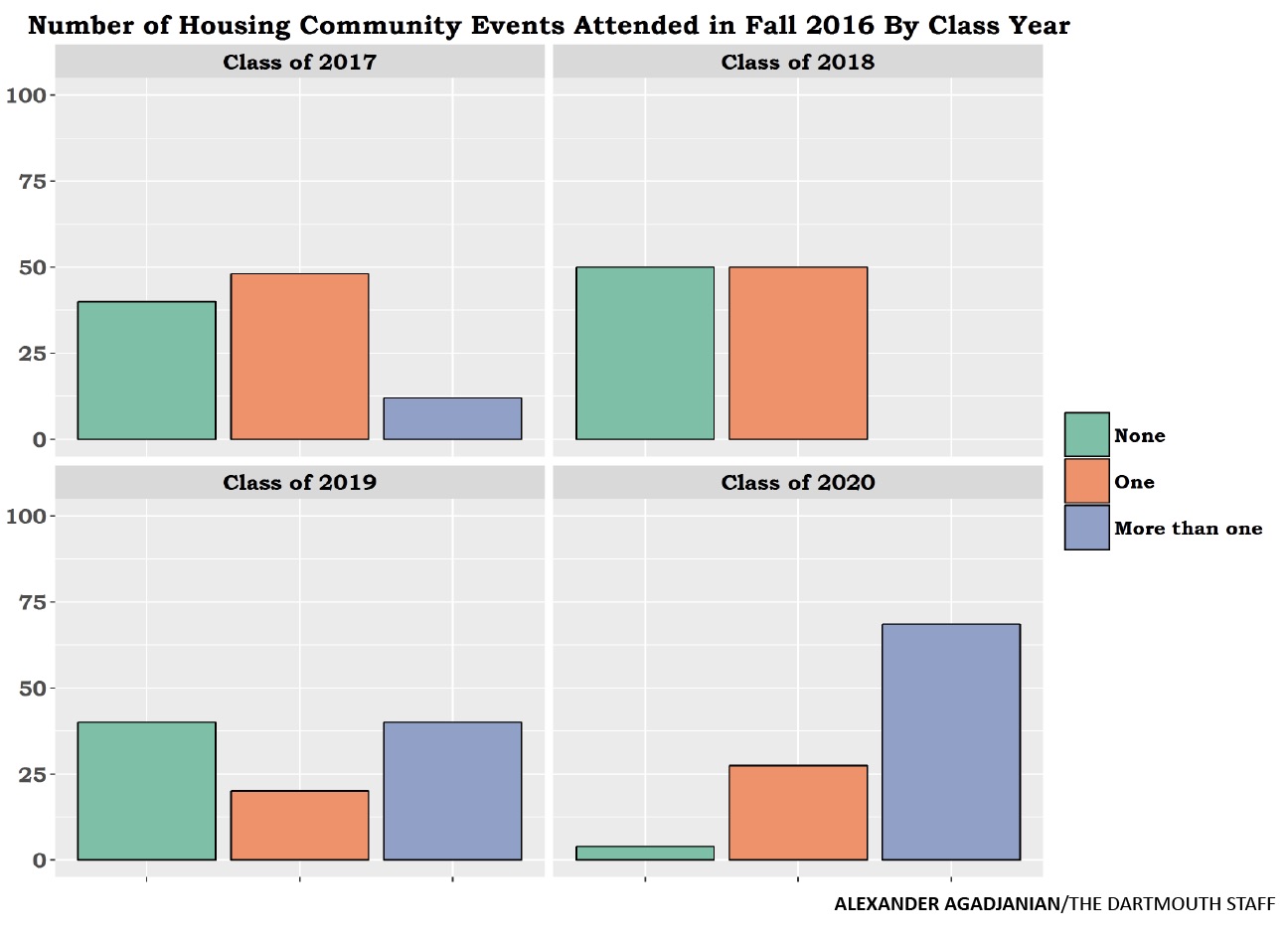

In a recent survey conducted by The Dartmouth, 46.2 percent of students surveyed had a favorable view toward the new housing system, while 17.1 percent had an unfavorable view. Yet despite this numerical admittance of favorability, the survey found that the housing communities continue to face issues with engaging upperclass students.

Event attendance drastically differs between upperclassmen and underclassmen. The survey found that 40 percent of ’17s have not attended any events, while 48 percent have attended just one. Fifty percent of the surveyed ’18s and 40 percent of the surveyed ’19s have attended none of the events. However, 86.6 percent of surveyed ’20s have attended more than one of the housing community events.

“There is a certain level of enthusiasm among the ’20s and the ’19s regarding the communities because they’re the ones invested in it,” School House professor Craig Sutton said. “They don’t know any different.”

Despite living in first-year-only residential housing, Daniella Kubiak ’20 said that members of her class are making an effort to bond with others in their houses, as they know that they will be living with one another in the coming years. She has gone to ice cream socials for her house in the Choates, she said, though lately she has been too busy to attend them.

Building a social and intellectual community is one of the main goals of the house professors. Allen House professor Jane Hill hosted a subset of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra in her home earlier last week. Ten students and seven faculty members attended the event.

Other events hosted by the different housing communities include an apple picking trip, intramural sports teams, dance and musical performances, a barbecue class on how to smoke meat taught by computer science professor Thomas Cormen and a presentation by war photographer James Nachtwey ’70. East Wheelock House professor Sergi Elizalde also hosted a dinner for those affected by the Morton Hall fire.

Elizalde said that an average of 20 students show up to the community’s events.

“We are aiming to create this vertically integrated, intellectual community where there are not a lot of boundaries separating students and faculty in the events,” Sutton said.

However, upperclassmen seem to be less inclined to participate. As a Dartmouth student who has been off for the past two terms, Matt Ferguson ’18 said he was not a part of Founder’s Day in the spring in which students found out their house assignments and has not been involved in with his house community.

“It was never part of my Dartmouth dorm experience and never will be,” he said. “I don’t feel involved whatsoever.”

Ferguson added that he feels guilty because his house professor is excited about the community building events, yet he does not participate in them.

Noah Manning ’17, a member of West House’s student working committee, said he strongly believes in the merit of residential life.

“We all acknowledge that upperclassmen buy-in is going to be a tougher part of this process, but I think there is an upperclassmen buy-in,” he said.

Manning argued that the housing community programming acts as a complement to student life. Because many programs are hosted within student dorms, upperclassmen living in those houses can easily wander in and participate, he said.

Yet the formation of such communities has faced structural obstacles.

“Right now, we are trying to graft a system onto existing facilities,” Sutton said. “As fundraising occurs, we will be able to build a residential system that actually fits this housing model. We are in a transition period.”

The housing communities, specifically East Wheelock, have also had issues with housing all of their students. Thuyen Tran ’19 is currently living in the Channing Cox senior apartments instead of in her own housing community.

“Because I had such a low priority number, by the time it was time for me to choose my room, there were no rooms left for me in East Wheelock,” said Tran. “I got into [Living Learning Community] housing, but they also waitlisted me because there was no room for me in the fall.”

The housing department told Tran that she could wait for someone to change their D-Plan and then move in or live in Channing Cox.

“Sophomores are guaranteed housing and they had no availabilities in my community,” Tran said. “A week before I needed to be on campus, I was really freaking out.”

Ryan Spector ’19 is also a member of the East Wheelock housing community. Rather than living in the senior apartments, he and his roommate are living in a converted study room in McCulloch Hall.

Like Tran, Spector and his roommate also had poor housing numbers. They were unconcerned because they were on the waitlist and the College guarantees sophomores housing.

During the summer, however, Spector and his roommate would receive weekly emails from director of housing Rachael Class-Giguere indicating that no housing was available. Class-Giguere gave the two the option of living in Channing Cox.

“When they were able to finally get us a room, it turned out that it was a study room that had been converted to serve as a residence,” he said.

Spector feels that the conversion of the study room into a residential space has had several shortcomings.

“The whole back wall and door are windows,” he said. “Also, each room has a placard outside the door saying its room number and ours says ‘Study Room.’ Two people entered the room by accident during the first few days of living there.”

Spector expressed dissatisfaction with the arrangement.

“It’s unacceptable, to be totally honest,” he said. “I was essentially told there were no other options because there are so few living arrangements on campus.”

Class-Giguere noted that each housing community has more students than beds. This was planned because not all members would be enrolled at the same time, nor would all of them want to live on campus, she said. She added that during fall term students are over-enrolled.

“Even before the housing system, when we don’t have enough space, we have to look at other options,” she said. “The enrollment is so high and the demand is so high; it exceeds what we have readily available.”

Despite the bumps, professors are optimistic about the potential of the new housing system. Elizalde served as faculty associate for the East Wheelock cluster before the implementation of the new housing system, the cluster was a standalone community structured similarly to the new houses. He attributed East Wheelock’s strong sense of community to the interconnected structure of the cluster.

“With the house communities, hopefully there will be six of these,” he added.

By: Sofia Stanescu-Bellu

As a Romanian immigrant and someone that has lived in multiple places, I always find it hard to build an attachment to a location or refer to it as “home.” Growing up living a few years here, a few years there made my life sporadic, to say the least: I’ve changed schools eight times, lived in three countries and have never spent more than four years in one place. But while I can’t call Vancouver, British Columbia or Grand Rapids, Michigan home, I can definitely call Romania home. This seems to contradict my previous statement. How can I call Romania home when I only spent my first four years there and barely spent five summers visiting?

For me, home is tradition. While I haven’t spent a significant time in Romania, Romanian traditions are the closest thing I have to that feeling of comfort and security that is “home” — a connection my parents built through my childhood that remains strong to this day. I grew up speaking Romanian, listening to Romanian Christmas carols during the holidays, dyeing eggs the traditional red-onion red at Easter, receiving a Martisor on the first of March and so much more. Even when I moved across the country, Romanian traditions remained a constant in my life, connecting me to my homeland. Places change but traditions don’t: traditions remain as a link to important places in our lives, and traditions are what define our “home.”

You’d think college would be different, and in fact, for most people it is. The vast majority of the population that goes to college spends four years in a place, builds friendships, gets a degree and moves on — much like my childhood spent moving around. There isn’t a significant connection to their alma mater save for one or two stray pieces of college gear stuffed in the back of their closet or worn to the gym and maybe a few football games spent cheering on their home team. You would probably find that most people can’t call their college home because it didn’t leave a lasting impact on them. Dartmouth, however, is different.

Dartmouth ranks second on the 2016 Grateful Grads Index, and its alumni network is consistently ranked as one of the strongest of any college in the United States. For Dartmouth, the annual Homecoming weekend has a deeper meaning than just the football team’s last home game of the season — it’s the weekend when hundreds of alumni make the trek up to Hanover to visit their alma mater — their home. It’s evident that alumni feel a strong connection to Dartmouth and that connection is important enough for them to come up to visit from all across the country and the world. So what is it about our small college in the middle of rural New Hampshire that keeps people coming back year after year? Tradition, of course.

Dartmouth is incredibly proud of its traditions, and they are the forum through which each class bonds with members of its own year and members of the years that came before it. The first experience we as freshmen are treated to is the Dartmouth Outing Club’s First-Year Trips: five days of getting to know members of our class and bonding with older students serving as Trip leaders in the beautiful northeastern wilderness. I know for me, Trips alleviated any fears that I had about college and made yet another move across the country easier. I am sure that the same can be said for almost all of the students who sign up for Trips. There’s a reason why 91 percent of incoming freshman participate in trips: word gets out that it’s a great experience and it becomes a cherished tradition.

Sophomore Summer, Winter Carnival, Class Day and, of course, Homecoming serve as further bonding experiences. Homecoming Weekend especially seems to foster a strong sense of community between current students and alumni. Speeches are given, alumni parade by class year and the famous bonfire is held. That year’s freshmen run around the bonfire to the cheers of the crowd and the night is alive with a feeling of excitement and unity. Just like matriculation officially initiated us into the academic side of Dartmouth, Homecoming official initiates us into the Dartmouth family. The experience marks us as full-fledged members of an incredibly long line of successful people that dates back over two hundred years. At Homecoming, we both participate in tradition and become a part of the tradition.

Some might argue that there are some unfortunate aspects of Dartmouth traditions that take away from the idea of community, but we shouldn’t let a few negative aspects of Dartmouth traditions ruin all of the positivity they have to offer. I agree that there have been some issues in the past, but the College has come a long way since then. Times have changed, and Dartmouth has seen the error of its ways and begun to make amends.

These traditions, moreover, set Dartmouth apart from other colleges. While other colleges are only there to educate their students, Dartmouth is also here to provide a home. At Dartmouth, the only feeling I’ve encountered in my short time here is one of community and acceptance. Everyone, from the professors to the students to the administration, has been incredibly friendly and welcoming, eager even, to have us ’20s join in on Dartmouth traditions and become members of the Dartmouth family.

On the eve of yet another Homecoming, I urge you to reflect on the traditions that make Dartmouth a home for many and appreciate the love the alumni and students share for this little college in rural New Hampshire. Finally, to all alumni and students, welcome home.

By: Carolyn Zhou

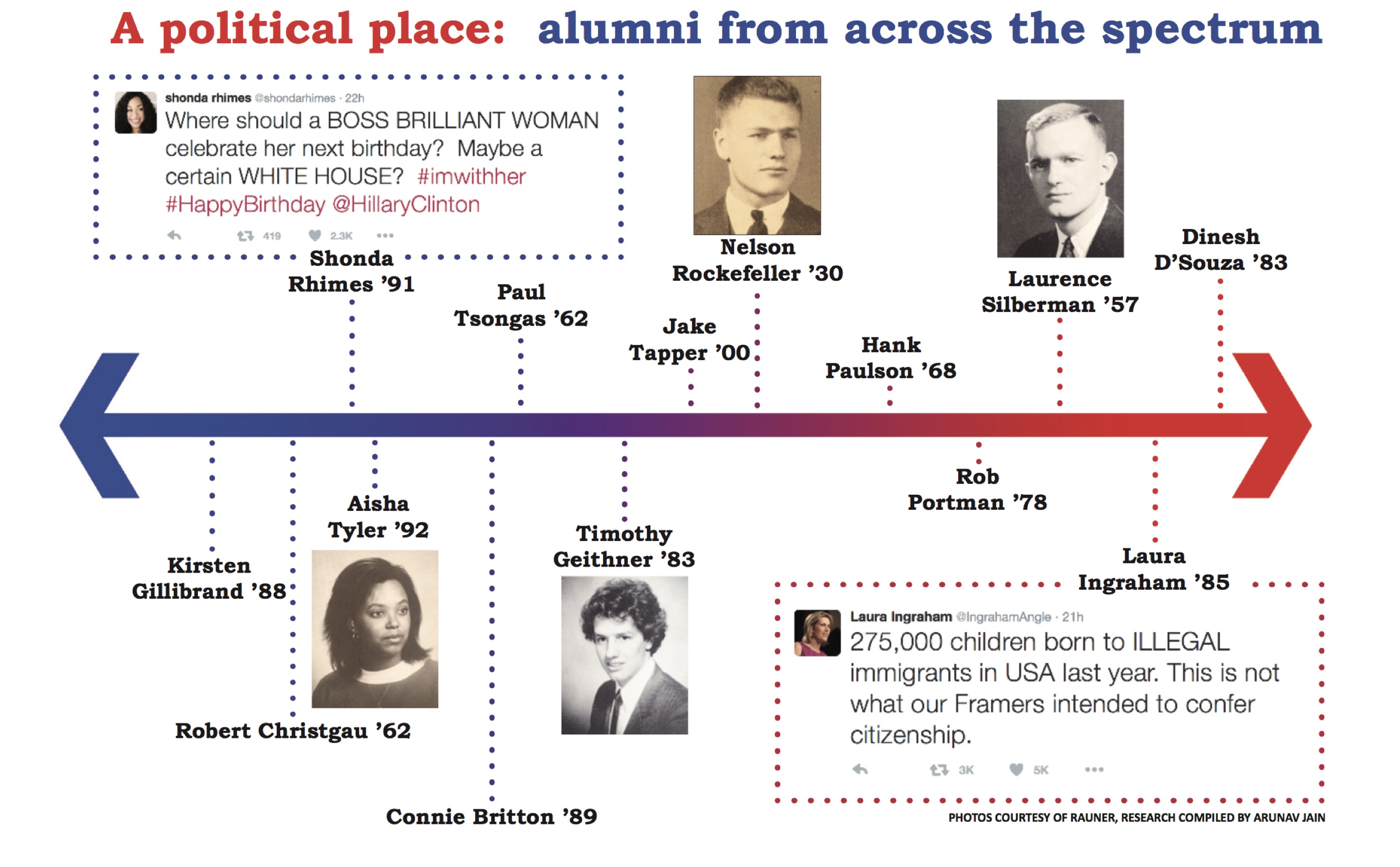

There’s no denying it: Dartmouth has a political reputation. In its infamous 2012 hazing exposé, Rolling Stone put it this way: Dartmouth “has stood fast against many… movements for social and political progress.” In a 2009 article on college stereotypes, The Daily Beast proclaimed, “Dartmouth has long been known as the most conservative Ivy.” It’s a notion circulated on college forums and by word of mouth, something you might even have heard when you were applying to Dartmouth.

Yet a recent survey by The Dartmouth hints otherwise. In response to a question about political ideology, 66 percent of 131 students identified as liberal, 19 percent as moderate and 14 percent as conservative. By the numbers, the College — like many other universities across the country — is hardly a bastion of conservatism. So why does that idea persist?

Charlotte Blatt ’18, president of the College Democrats, offered her take.

“It’s a misguided stereotype”, Blatt said. “We’re rural, we kind of have a prep-school vibe, there’s definitely old money associated with Dartmouth… these things make Dartmouth seem more conservative than a school like Brown or Columbia.”

Also underlying Dartmouth’s conservative reputation is the fact that the College was one of the last members of the Ivy League to admit women, in 1972. The decision was not without controversy, especially at a school that clings so tightly to tradition. Even years after coeducation, this legacy remained in the mind of the public and was tangibly felt by student body.

Writing professor Julie Kalish ’91 recalled that when she made the decision to come to Dartmouth some people raised their eyebrows.

Kalish’s experiences suggest that Dartmouth was somewhat more conservative in the past. Her sophomore year, which was in 1988, was the first time that the alma mater was officially changed to include women — 16 years after women were admitted.

Conservatism at the College also has an established voice in The Dartmouth Review.

“The Dartmouth Review is the first publication of its kind, and by far the most influential,” said Brian Chen ’17, an executive editor of The Review, speaking in a personal capacity. “That does not make the campus any more conservative, however. It’s just that conservatives on this campus have had more of an impact than conservatives on other campuses.”

The Review was well-organized and impactful from the get-go. Founded in 1980 with backing from famous author and conservative giant William F. Buckley, Jr., the publication received national attention very quickly.

“This was partly because the staff pushed controversial issues aggressively,” Chen said. “This conservative reputation kind of rubbed off on the entire school.”

During Kalish’s undergraduate years, she recalled, The Review was a huge influence. She said that the Review provided a voice that people paid attention to on campus.

Kalish recalled one such episode which occurred during her time as an undergraduate at the College. In January 1986, a group of 12 students armed with sledgehammers — the majority of them members of The Review, attacked shanties that other students had built on the Green. The shanties had been built to protest apartheid in South African.

In 1990, then-College president James Freedman told The New York Times, “When I am off campus, The Review is all people want to talk about, and they don’t realize The Review doesn’t have any real influence here at Dartmouth itself.”

Freedman appears to be partly in the right. Historically, The Review has been an outsized force in shaping the College’s public reputation. And although people may pay attention to what is published in The Review, survey results and student opinion suggest that the publication has had far less of an impact on the overall ideology of the student body. In fact, the student body may have become more consistently liberal over time.

Kalish said the prominence of conservatism in her undergraduate years led to the feeling of a split campus.

“The campus was significantly more politically polarized than it is now,” she said. “There was a dominant, large, conservative group of students on campus. And there was a visually distinctive, loud, radical left on campus...you couldn’t go to Dartmouth and not think about and not confront your positions on certain issues because there were such vocal and extreme groups.”

Both Blatt and Chen, who is also vice president of the College Republicans, agree that the liberalism prevails among today’s student body. But they differ on the level of political awareness, engagement and activity among current Dartmouth students.

“Dartmouth’s student body by and large knows major political news pretty well,” Blatt said. “That being said, I don’t think that a majority of Dartmouth students are directly involved with campaign activities.”

Chen, on the other hand, sees a majority of students that is to some degree politically apathetic.

“Dartmouth has a very privileged student body, and part of being privileged means that you won’t care about politics because you’ll be fine either way,” he said. “[At Dartmouth,] you’re located in the middle of nowhere, in Hanover, New Hampshire, far away from any major city. It’s a very insular place.”

But undeniably, political tensions exist on campus, echoing the similar divisiveness in our government and country today. Blatt suggests that the strain comes from a lack of communication between different circles.

“A lot of that tension comes from lack of inter-group dialogue on campus,” she said. “There are pockets of different identities that hang out with each other, and lack of communication between different groups leads to tension.”

Sometimes, those tensions can make it difficult to be publicly conservative on campus. Blatt said that on a campus that favors a progressive dialogue, being conservative can carry a social cost, especially for someone who takes an outspoken position on social issues.

“Expressing a conservative sentiment, like being against gay marriage, would probably be something that would get a negative reaction on this campus,” she said. “That being said, I don’t think there’d be a negative reaction against someone if they said, ‘I’m a Republican, I’m a conservative.’”

But politics have influenced some of Chen’s relationships. “Personally, there are people who do not like me, who will not be friends with me, solely because of my political views,” Chen said. “I recognize that some people have strong feelings, and they express those feelings in ways that I might not agree with.”

Chen does not allow this to constrain his words or actions, but he says many do.

“[On campus,] there are limits to what you can say in public,” he said. “There are some people who keep silent because they’re scared that they’ll lose friends or people will look at them funnily.”

Emma Marsano ’18 is a co-founder of the Dartmouth Political Times, a new publication which hopes to address this sort of divide.

“There are issues that people can come together on,” Marsano said. “The vitriolic conversation [going on] nationally…is not productive. I think that we can rise above the party politics mentality.”

Conservatives may have a smaller footprint on campus than they did 30 years ago, but their voice is still heard. The Review persists as a mouthpiece for conservatives on campus, one that stirs up impassioned debate — as it did last year in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests. It still rings true that by being on campus, one’s values, morals and beliefs are challenged, whether one is forced to think about these issues when they are spread across the headlines of the Review or The Dartmouth, or when the tension that still exists bubbles up and finally bursts out.

Marsano is a member of The Dartmouth business staff.

By: Kaina Chen

It’s largely true that pursuing a college degree opens doors to otherwise inaccessible careers and opportunities. Based on a report by the Economic Policy Institute, recent college graduates face an unemployment rate of 7 percent, while recent high school graduates face an unemployment rate of 20 percent.

But while these options are a blessing, they come with the responsibility of choosing which doors to open and which ones to close when embarking on a career after graduation.

Fifty-one percent of Dartmouth’s Class of 2016 went into finance and consulting. Peer institutions boast similar statistics. Thirty-nine percent of Harvard University’s most recent graduating class and 49 percent of last year’s graduating class at Cornell University also went into these fields.

But there hasn’t always been a rush to Wall Street after graduation. In the 1970s, many graduates from elite universities pursued medicine, law or public service, said Bill Deresiewicz, the author of “Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life.”

Yet for Dartmouth’s Class of 2016, only 4 percent are pursuing law, 7 percent health and science and 2 percent governmental or military work.

By the 1980s and beyond, large numbers of students were pursuing finance and consulting, said Monica Wilson, senior associate director of the Center for Professional Development. In the 1990s, insurance companies, oil and gas companies were prominent, Wilson added.

In merely 50 years, the face of young adults’ postgraduate careers has undergone substantial changes, both at Dartmouth and elsewhere.

Many career services departments at colleges and universities partner with employers. In return for programming, scheduling services and offering preferred dates to host events, employers compensate career services departments.

“Employer funding has different forms,” Wilson said. “There are fees for services, payment for a package of services, gifts or opportunities to showcase their company’s goods — such as the furniture provided by Wayfair.”

“Ninety-five percent of our employers come from out of state, and have to make the trip up to Hanover,” said Roger Woolsey, director and senior assistant dean of the CPD. “They’re spending a lot of money to communicate with the best talent. They want a good-sized audience.”

This can create a perception that students are being “funneled” into the consulting and finance silos, encouraged by programming from the CPD. However, Woolsey challenges that claim.

“We are not an academic institution that is making money off an industry vertical,” he said.

Wilson said that the CPD offers exposure to many types of industries, typically tailoring the form of exposure based their employer needs and student interest. For example, students can be exposed to non-profit or pre-professional careers through immersive experiences that allow students to engage with these industries off-campus.

Data also show that student choice plays a large role. In 2015, there were 923 job postings in the educational field, exceeding the 744 job postings in consulting. However, 10 percent of the Class of 2015 went into education while 19 percent went into consulting. It is evident that students prefer one sector or type of career over another.

If student choice is at play, what are these individual incentives towards the pull to Wall Street?

Wilson and Woosley, who have frequent conversations with students about career opportunities, say that students often enter industries to “open doors” or learn more about different career fields. They might stay in a field because they have become used to a certain income level, or leave to pursue further graduate degrees such as an MBA.

“People at fancy colleges have always been interested in making money,” Deresiewicz said.

This could be the case. Fifty-four percent of the Class of 2016 will earn more than $70,000 during their first year as a fully-employed adult. Fifty-three percent of Harvard University’s Class of 2016 will earn more than $70,000 while 38 percent of Cornell’s Class of 2016 will earn more than $72,000.

Yet the argument is a bit simplistic. Surely, whether students believe it or not, the common rhetoric of “find a job you love” often touted at commencement speeches has taught students that career fulfillment comes from more than one’s salary.

Student debt is not necessarily the answer either. Surprisingly, students at elite institutions are often in less debt than the sticker price of tuition would suggest. Full tuition at Dartmouth is approximately $250,000 for four years. Nationally, according to a report from the Project on Student Debt, the student debt load for the class of 2010 was approximately $25,000 in loans while Dartmouth students had about $19,000 in loans.

Maybe it’s a systemic shift that has caused the change.

“The college admissions process has changed American adolescence,” Deresiewicz said. “There’s much more careerism, the pursuit of status and wealth for their own sake.”

For Deresiewicz, the career shift is an emblem of an ideological shift. The reasons that people gave for entering fields of public service, such as “giving back” or “stewardship,” are still used today, but less genuinely, and more for face value than for real meaning, he said.

“People aren’t happy, and they’re working like crazy for rewards that are ultimately empty,” Deresiewicz said.

Yet there are those who are seriously committed to the path, as a decision they’ve purposefully chosen for themselves.

Amy Yang ’17 first became interested in consulting during her sophomore year.

“For management consulting, it’s challenging and opens up a lot of doors,” Yang said. “For consulting, part of the appeal is that as one moves up vertically, there is still a breadth of exposure.”

This sentiment of continuing to explore options was present in many of those interested in consulting and finance. Many view these commitments as temporary — graduates who enter these fields do not intend to stay. Voluntary industry turnover rates support this. For banking and finance, the 2014 voluntary turnover rate was above average, at 13.3 percent. The trend is not unique to finance — from the 2016 Deloitte Millennial Survey, 44 percent of those surveyed intend to leave their present careers in the next two years.

Others choose to delay commitment in other ways. Yichen Zhang ’17 intends to work in the biotech field before applying to medical schools. Zhang was unsure how long he would wait before applying — perhaps anywhere from one to three years.

Historically, this “exploring options” phenomenon is relatively new and extends beyond committing to a career. Sociologists define adulthood by five metrics: completing school, living independently, financial independence, parenthood and marriage. According to the United States Census Bureau, fewer than 40 percent of 30-year-olds passed these milestones in 2000, down from 70 percent in 1960.

Therefore, it could be that students are increasingly unwilling to settle down and value the flexibility in overall career paths offered by industries like investment banking and consulting.

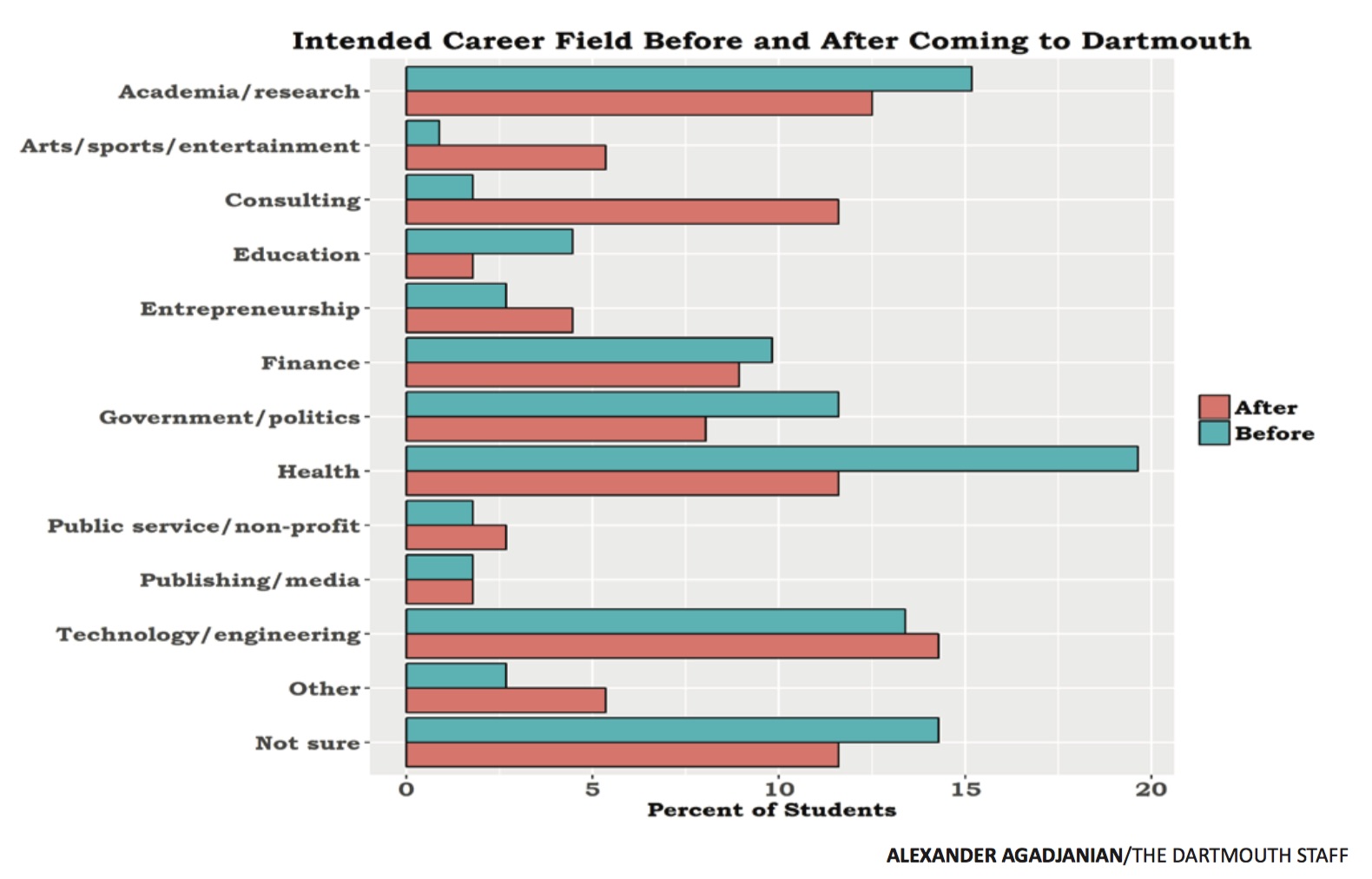

The Dartmouth recently surveyed the student body, asking them to compare career intentions before coming to Dartmouth and today. While approximately two percent of those surveyed intended to enter consulting prior to attending Dartmouth, 12 percent are currently interested in the field.

In contrast, interest in health-related careers tended to decline as students moved through their Dartmouth years. Approximately 20 percent of those surveyed intended to enter healthcare prior attending Dartmouth, while only 12 percent still intend to enter health-related careers.

For those who choose a path that’s not the consulting or finance route, there are consequences as well, such as “social and psychological pressure, defying parents, dealing with ridicule,” Deresiewicz said.

This shift, regardless of the reasons behind it, is unprecedented and undeniable, and has consequences.

“There are many smart people pursing these fields,” Yang said. However, she concedes, “It’s a bit of a loss to other career opportunities that also need these people.”

By: Zachary Benjamin and Evan Morgan

Tradition – the word is full of connotations, both positive and negative. For some, Dartmouth’s traditions are among their best experiences at the College, creating a sense of community and identity. Others think that those practices deserve closer scrutiny.

When we began brainstorming topics for this issue, we both thought that tradition was an obvious choice – though for different reasons. Evan was inspired by Shirley Jackson’s short story “The Lottery,” which ends with the stoning of an innocent woman to ensure a good harvest: a classic case of ritual gone wrong. Zach was disturbed by Evan’s macabre mind, but also thought tradition was an apt topic, given the ongoing campus dialogue about how best to improve Dartmouth.

We hope that the articles in this issue are informative in and of themselves, but we also hope that they inspire a broader conversation about the role of tradition at Dartmouth. Which of our traditions are valuable, and which, if any, should we move away from? No matter your thoughts, we encourage you to speak your mind. Dartmouth will never be perfect, but we hope you will work to make it the place you want it to be.

By: Anthony Robles and Samantha Hussey

As the days grow shorter and temperatures lower, the Class of 2020 will experience one of the College’s most storied traditions tonight: Homecoming.

The most significant aspect of Homecoming is the bonfire itself, born in 1888 to spontaneously celebrate a baseball victory over Manchester College. Many in the town did not regard this tradition highly. According to an article at the time from The Dartmouth, “[The bonfire] disturbed the slumbers of a peaceful town, destroyed some property, made the boys feel that they were being men, and in fact did no one any good.” The first organized bonfire occurred five years later to commemorate a 34-0 shutout of Amherst College by the football team.

Two years later, on Sept. 17, 1895 in Dartmouth Hall, then-College President William Jewett Tucker launched Homecoming, originally known as “Dartmouth Night,” as part of his “New Dartmouth” initiative. Tucker hoped that Dartmouth Night would become a tradition that involved the entire student body and united students with alumni since he felt that other traditions at the time, such as matriculation and Commencement, only recognized one class at a time.

On that Tuesday night, a host of alumni delivered speeches recounting their experiences at the College. Craven Laycock of the Class of 1896 read the poem “When Shall We Three Meet Again.” The celebration concluded with singing from the Glee Club.

At the next Dartmouth Night, Class of 1885 graduate Richard Hovey’s song “Men of Dartmouth” was deemed the best Dartmouth song and would later be recognized as the College’s official alma mater, according to documents from Rauner Library.

The celebration in 1901 was notable for its tribute to the centennial of Daniel Webster’s graduation. Webster, a politician who served as both a United States Senator and Secretary of State, famously defended the College during the landmark Supreme Court case Dartmouth College v. Woodward.

Dartmouth Night in 1904 featured the presence of both the seventh Earl of Dartmouth — great-great-grandson of the nobleman whom the College is named after — and Winston Churchill. The guests were treated to Dartmouth students running around the bonfire in their pajamas.

In 1907, because of the celebration’s increasing attendance, Dartmouth Night was moved to Webster Hall, now home to Rauner, where it remained for years until finally being moved to its current location on the Green.

One of the main components of the festivities is the alumni parade, which was halted after 1915 with the onset of World War I. The parade was not brought back for another 58 years.

Football began to play an important role in the weekend in the 1920s. Memorial Field was dedicated in 1923 during the celebration, and 13 years later the College began to schedule football games to coincide with Dartmouth Night. In 1946, a rally for the game against Columbia University was scheduled during the festivities.

The 1934 celebration honored Edward Tuck, a member of the class of 1862 and son of Amos Tuck, the namesake of the Tuck School of Business, according to documents from Rauner. Tuck was the College’s greatest living benefactor at the time.

World War II again brought change, toning down Dartmouth Night celebrations. The 1943 celebration moving from Webster Hall to Thayer Hall, documents from Rauner said. There was no traditional speaking program, and the entire event resembled a reception, with music provided by the Glee Club and a small string ensemble.

The 1950s saw the birth of the star-hexagon-square structure that remains in use for the construction of the bonfire, according to the manual currently used to construct the bonfire. Previously, students used piles of scrap wood.

The bonfire was canceled in 1954 due to Hurricane Hazel, and again in 1963, when the worst dry spell in over 100 years prompted the Hanover Fire Department to halt celebrations.

A lack of student interest and increased agitation towards the Vietnam War in 1969 resulted in Dartmouth Night being canceled entirely for the first time ever. It was not officially celebrated by the College again until 1973.

Gathering sufficient amounts of wood for the bonfire has never been a simple task. The Dartmouth previously reported that in 1971, a local farmer allowed students to use the wood of his barn for the bonfire. An error in directions resulted in the students tearing down the wrong farmer’s barn.

Moreover, up until the late 1980s, it was a tradition for the number of tiers to equal the year of the first-year class, according to the bonfire manual. However, as class years became larger and larger, the structure became taller thus more unstable and dangerous, which forced the College to cap the bonfire’s height in 1990. Following a bonfire accident at Texas A&M University in 1999 where 12 students died and 27 were injured, the College was forced to play a bigger role in the construction. Students at the Thayer School of Engineering designed the structure that is used today that ensures structural integrity and overall safety.

In 1988, after nearly a century of existence, Dartmouth Night was renamed Homecoming, and the moniker stuck.

Now in its 121st year of existence, Homecoming remains an integral part of Dartmouth tradition, not only for the incoming freshman class, but for those who have long since graduated. On one of the biggest weekends of the year, the longstanding tradition that brings together alums from all over the world recalls the words of Webster.

“It is a small college,” Webster said. “And yet, there are those who love it.”

By: Clara Chin

With J.D. Salinger’s “The Catcher in the Rye” in one hand, mason jar filled with cold-brewed coffee in another and headphones blasting the latest indie track, many college students are quick to identify against mainstream culture. In a frenzy to shape our identity as adults, we often feel the need to refine our outward attributes to immediately shout “pop culture” or “counterculture.” While the stereotypes attributed to each differ, both reveal a universal anxiety to identify with others like ourselves. This year, it’s not just our taste in music and clothes that speaks to how mainstream or underground we are but our choice in political candidate as well.

Many people assumed that the presidential election of 2016 would be an “establishment” race between Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush — but it was Donald Trump who ultimately became the Republican Party candidate for president. Though Clinton won the Democratic primary, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders shook up the race and won more votes than many thought possible for a self-described socialist. Sanders’ and Trump’s large followings and relative successes seemed to awaken a revolutionary spirit among those who felt neglected by mainstream politics. For the first time, many people felt empowered by their differences rather than estranged. But defining Clinton as the establishment candidate compared to her Democratic and Republican competitors underestimates her countercultural power while demonstrating a widespread, simplistic understanding of what may be considered as such.

Even though Clinton is not typically described as counterculture, she is not necessarily mainstream. After all, she could be the first female president — disrupting our country’s 227-year-long tradition of only male presidents. Much in the same way that President Barack Obama’s election forced us to consider difficult but necessary questions about race relations in the United States, a Clinton presidency is likely to continue raising questions about gender — her campaign has already led to questions about double standards. Although she has been in politics for many years, let’s not forget that she expressed positions on women’s equality early on in her career that were considered radical and now form the basis of her current policies. Her leadership strategies are also untraditional: political blogger and columnist Ezra Klein describes her skills as a listener, which run in contrast to many previous presidential candidates, who typically led by talking.

A Clinton fan who recognizes elements of the counterculture in her campaign created a video about Clinton using Bikini Kill’s feminist anthem, “Rebel Girl.” Aside from the creator’s possible breach of ownership rights and the fact that Bikini Kill founder Tobi Vail eventually filed a copyright infringement notice, the pairing is actually perfect. I initially reacted to the video with distaste. While I enjoy Bikini Kill and support Clinton, I wanted to put them in two separate spheres for what I then considered two separate sides of my personality — angry feminist music in my personal life and cool, calculated feminism in politics.

But in a perfect world where Vail did not take down the video, the mash-up is a testament to the clashing and meshing of culture and counterculture across various times and spaces. Their feminisms are not separate, but related and codependent. Clinton’s statement that “women’s rights are human rights” at the United Nations Fourth Global Conference on Women may not have been possible without the musical rage of singers like Vail and Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth. Clinton helped to bring a feminist revolution based in music to a feminist revolution in politics, transforming feeling to policy.

Counterculture and mainstream culture create tension, but they also intertwine, overlap and define each other. Clinton herself is the best example of this: although she is an establishment candidate to some extent, she also fights the power. Clinton, who embodies mainstream American politics, needs to be pushed directly by more radical activists and indirectly by art movements. Clinton, who embodies an outsider in American politics, also helps to push feminist issues forward. Clinton’s UN speech, once radical and now not so much, reminds me of parallel cycles in my favorite art forms — of how Chopin’s now romantic music was once considered strange and too emotionally charged, how the weirdness of David Lynch films came to establish an American film tradition and how the rebelliousness of Nirvana has since been replicated in newer bands. In the same way, Clinton has not been and even now is not as mainstream as many seem to think. To the extent that she is mainstream, it’s only because she has worked hard to normalize her beliefs and subvert patriarchal traditions, and we should keep this in mind as Election Day approaches.

By: Mikey LeDoux

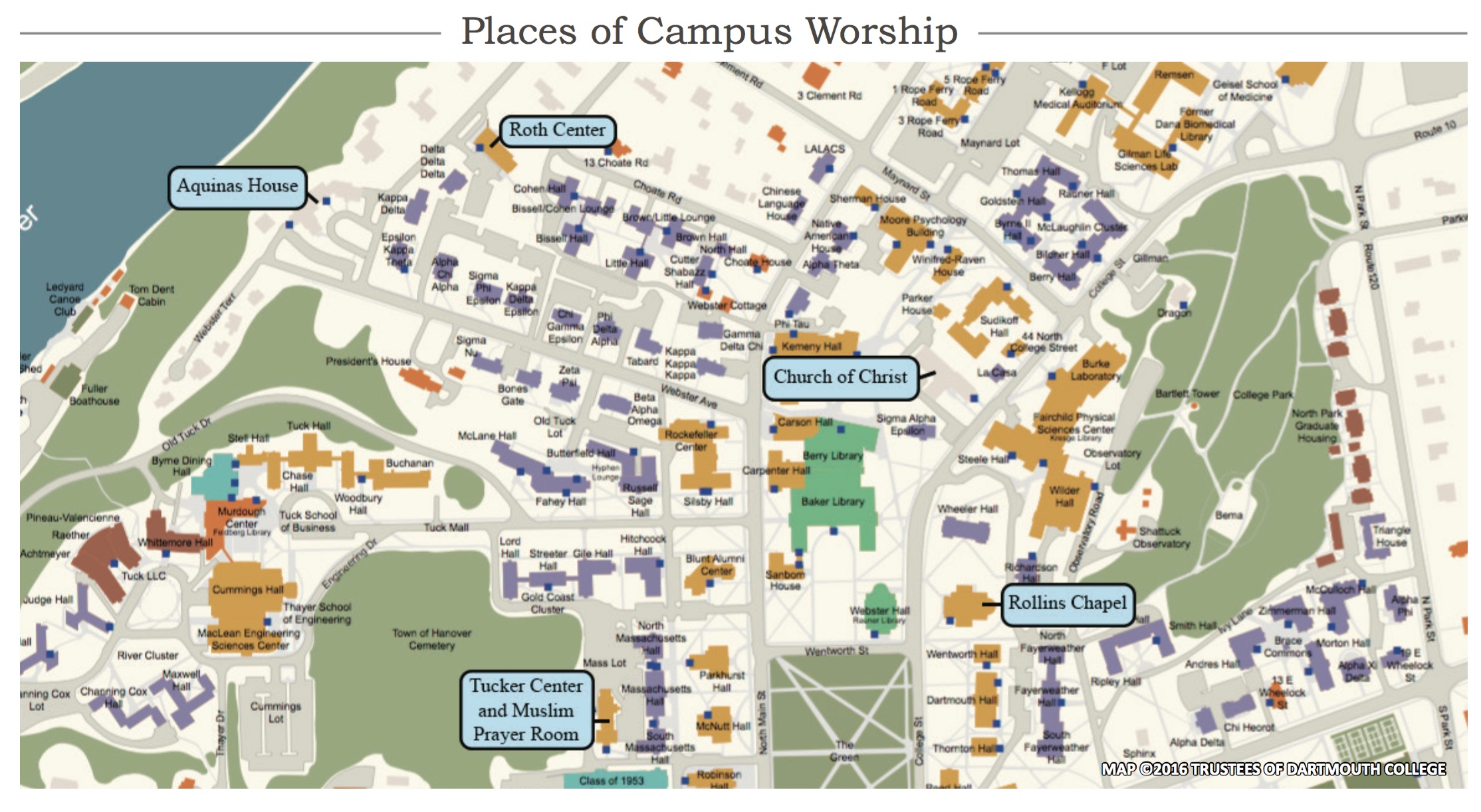

Eleazar Wheelock, who also founded the College, gathered the congragation of The Church of Christ in 1771.

Eleazar Wheelock founded Dartmouth in 1769 as a college affiliated with the Congregationalist church, a branch of Calvinism. In fact, the mission of the College upon its founding was to educate Native Americans to become Christian missionaries. Dartmouth is not unique in this respect — other Ivy League universities were also founded with a religious affiliation. Today, however, no member of the Ivy League is associated with a certain religious group.

Christian-based groups continued to dominate the College until the mid-20th century. In 1801 the Student’s Religious Society, the first religious campus organization, was founded in response to a perceived lack of religiosity on campus. Until 1903, attendance for Sunday mass was compulsory. According to an article from a 1977 edition of The Dartmouth, the College gave students an option to elect the clause, “in the year [insert year]” instead of the religious clause, “in the year of salvation of mankind, [insert year]” for their diplomas. This was seen as a sign of the College becoming more inclusive of all religious traditions. From the 1970s onward, non-Christian religious groups’ presence continues to grow at Dartmouth.

According to the Pew Research Center, 48.3 percent of Americans identify as non-Catholic Christian, 20.8 percent as Roman Catholic, 1.9 percent as Jewish, 1.6 as Mormon, 0.9 percent as Muslim, 0.7 percent as Buddhist and 0.7 percent as Hindu. Those who are atheist or agnostic make up 3.1 percent and 4 percent, respectively, while 15.8 percent of Americans identify as “nothing in particular.”

On the College’s 2016 survey of first-year students, 17 percent of students identify as Protestant, 9 percent as another type of Christian including Mormons, 19 percent as Roman Catholic, 9 percent as Jewish, 1 percent as Muslim, 1 percent as Buddhist and 3 percent as Hindu. Thirty-three percent identify as either atheist or “none.”

Today, an active network of organizations offer students opportunities to practice religious traditions and observances of all types at Dartmouth. These groups are noteworthy for their openness and acceptance of anyone, regardless of their religious background. This creates a unique and welcoming environment for members of the Dartmouth community who want to continue practicing a religion or are interested in exploring a new one.

Students find different ways to observe their religion while at Dartmouth. The following vignettes were taken from a small sample of undergraduate and graduate students at Dartmouth and represent only their personal experiences.

Buddhism

Rollins Chapel offers resources for multiple religions.

Jingwen Liu ’18, an international student from China, grew up in an atheist family. However, her freshman year roommate, who was a Christian, inspired Liu with her dedication to her faith. During her freshman summer, she attended a summer camp where Buddhism was taught casually. When she studied abroad in Berlin, she went to a Buddhist temple, which helped her cope with the culture shock of living in a foreign country.

“The Buddhist text is so powerful,” Liu said. “You feel changed in a non-mental way — like a revelation.”

Liu returned to campus and became more involved with the Zen Practice Group, a Buddhist organization on campus, which is small and made up of mostly graduate students. Allyn Field, founder of the Upper Valley Zen Center in White River Junction, leads the group’s informal sessions, which consist of meditation and discussion.

Liu appreciates how Field clearly articulates relatable advice that contains Buddhist insights.

“What he says is common sense, but when you’re stressed, you forget common sense,” she said. “Since deepening my understanding of Buddhism, I have resonance with his words more and more.”

Catholicism

Aquinas House is Dartmouth’s Catholic campus ministry. Located near the end of Webster Avenue, Aquinas’ physical plant is the site of both religious and social programming.

For Richard Williams ’18, who attended a Jesuit high school, having a Catholic community was a priority when choosing colleges. Several of his high school peers recommended Dartmouth as a school with a strong Catholic student center.

Approximately 200 people attend Sunday mass, held at 11 a.m. and 7:30 p.m. On Mondays, Aquinas hosts a student-cooked community dinner, a popular event that brings in about 50 people each week.

Just as with the other religious groups on campus, Aquinas welcomes all students at all levels of involvement. Some students dedicate all of their free time to the group while others only come to mass, said Meg Costantini, the Aquinas campus minister.

Other events include film screenings and dinners with professors to discuss their interests in topics related to faith. Costantini said the series gives students a chance to converse about “cultural creations that speak to questions of faith.”

Community service projects provide opportunities for students to practice their faith actively. These outreach activities allow students to “live out what Jesus taught,” Williams said.

Williams considers the Catholic community at Dartmouth to be very active. He enjoys his role as one of the “Faith and Reason” student leaders who facilitate weekly discussions on different aspects of the faith. The group allows students to share thoughts and learn from each other’s perspectives, which has deepened his own faith, Williams said.

Hinduism

Shanti, which means “peace” in Sanskrit, is the Hindu organization on campus. Established in 2002, Shanti’s mission statement declares the organization’s dedication to promoting the universality of all religions. The organization’s advisor is computer science professor Prasad Jayanti.

Anup Joshi, a doctoral candidate in the computer science department from India, was interested in joining a Hindu group when he came to Dartmouth.

“It was good to have such a group, especially for people coming from India because the U.S. is such a Christian environment,” Joshi said.

Shanti hosts daily pujas, or prayer rituals, in the Hindu temple inside Rollins Chapel. The organization also sponsors cultural events that are open to all of campus, such as celebrations for Holi and Diwali. They also host smaller festivals, such as Ganesh Chaturthi.

“In Shanti, I get to meet people who, from childhood, celebrated the same holidays as me,” Joshi said. With these types of connections between members, “you don’t feel lost from your culture and you still feel at home,” he said.

Islam

Al-Nur, Dartmouth’s Muslim student association, was established in the early 1980s, according to its website. With about 80 Muslim undergraduate students, Al-Nur typically has about 15 to 20 active members throughout the year, said Wassim Hassan ’19, vice president of Al-Nur.

Hassan transferred to Dartmouth from the University of Illinois at Chicago, which has a robust Muslim student association. Islam has always been an important part of his life, and Hassan was involved with his hometown’s local mosque. Prior to matriculating, Hassan prepared himself to find a smaller Muslim community at Dartmouth, but upon arriving, the small size of the community still surprised him. The difference in size, however, comes with benefits. The Dartmouth group, he noted, is a tight-knit community.

“It was a big change, but it was good,” he said. “Everyone knows each other [here] and it’s a more personal experience.”

Due to the small size of the community, members of Al-Nur may feel pressure because their individual actions influence people’s opinions of the faith, he added.

“We’re a beacon and representation of the faith to everyone on campus,” Hassan said. “I have to be conscious of my actions.”

Given the current political climate and the harsh rhetoric surround Muslims in the United States, Hassan said, the members find solace in supporting one another to adhere to the faith despite how others perceive them.

“We show each other this isn’t who we are, but this is how the media portrays us,” he said.

Every Thursday, the organization hosts “Thursday Night Think Tank” at the Tucker Center, which brings students together in a casual environment to converse with each other on various issues as they navigate contemporary society.

“As Muslims, growing up we don’t question things necessarily […] it is seen as taboo to ask certain questions,” Hassan said. “At our age, this is the time when you’re exposed to the real world and that makes you question things that have been fundamental to your beliefs. It is dangerous to do that on your own, so having a support group is important.”

Judaism

Dartmouth College Hillel and Chabad at Dartmouth provide students with opportunities to develop their understanding of and connection to Judaism through a mixture of social and religion-based programming.

Sam Libby ’17, president of Hillel, came to Dartmouth from a non-sectarian, Christian school.

“Freshman year, I fell in love with the community,” Libby said. “I wanted to give back and make sure everyone had [as great] of an experience as I had.”

Hillel hosts gatherings for Jewish holidays and social events. They hold Shabbat dinners celebrating the Jewish day of rest every Friday, which sometimes includes a guest professor who speaks with the group. The group’s rabbi, Edward Boraz, also holds a weekly Torah study.

Libby remarked that although Hillel has one rabbi, one administrator and one director of donor relations, they are still able to offer a wide range of programming for students.

“You can take advantage of Hillel whether you step foot in the Roth center or not,” Libby said.

Eliza Ezrapour ’18, president of Chabad, came to Dartmouth from a Jewish Day School and wanted to be involved with the Jewish community at the College.

“I think it was a benchmark of comfort to be a part of a community that would cater to that part of my identity,” said Ezrapour.

College has given Ezrapour a different perspective on practicing Judaism.

“When you come to college, you are facilitating religion for yourself without your family or classmates,” Ezrapour said. “It requires a stronger sense of agency.”

Chabad also hosts Shabbat dinners on Fridays, as well as other social programming. Rabbi Moshe Gray regularly meets with students for coffee to talk about everything from religion and social and academic questions.

“Dartmouth is a small enough school where you can have a serious impact, which you couldn’t have at a bigger school or through bigger events,” said Gray.

Mormonism

The Latter Day Saint Student Association supports Mormon students at the College. The group has approximately 10 undergraduate and two graduate student members.

Sarahi Pineda ’18 has been involved with her local LDS church for her whole life and came to Dartmouth excited to become part of the campus group. The organization gives Pineda a community she finds commonality with.

“I definitely have a lot of friendships outside of the group, but I like [being part of the group] because it’s a reassurance that you’re not the only one,” she said.

On Sundays, the group travels to an LDS church off campus. Later that night, they have a community dinner, followed by study sessions where they read and discuss important religious texts, such as the Old Testament and the Book of Mormon.

Spencer Hatch, a fifth-year graduate student in the physics and astronomy department, came to Dartmouth from Utah. He found that attending a school in New England with few Mormons strengthened his identity.

“Coming from Utah, where there is a background of that faith everywhere, I didn’t know what it meant to have that identity since it was the common identity but here it means something,” Hatch said.

When fellow students find out that Pineda is Mormon, the often ask a slew of questions.

“The Church teaches us that it’s good to talk with people because it helps clear up a lot of misconceptions,” Pineda said.

She noted while it is hard to be on a campus when the climate sometimes opposes her beliefs, she feels accepted by her friends and others on campus.

“I have never felt pressured to participate in activities I don’t believe in,” Pineda said. “That is totally a Dartmouth thing — to accept people for who they are and make everyone feel comfortable on campus.”

Protestantism

Agape Christian Fellowship, with a membership of around 50 students, is one of the Christian groups on campus.

Arun Ponshunmugam ’17 has found his place at Dartmouth with Protestant groups like Agape. One of Agape’s main events is a weekly prayer and worship gathering on Fridays. There, after the worship, someone shares a story from his or her life that demonstrates his or her relationship with God.

“Agape focuses less on religion and more on cultivating a relationship with God through forming a daily prayer life,” he said.

In addition to religious activities, Agape also hosts more casual social events for its members, including Fort Diner visits, the Lou’s challenge and stargazing.

“We’re more like a family than a group of friends,” Ponshunmugam said.

Ponshunmugam said that he sometimes feels like he has to hide the fact that he is religious.

“I think there might be a misconception that religious people are bigots or closed minded and I hope that I am actively breaking this stereotype,” Ponshunmugam said. “But most people are very open to me praying for them and talking about religion in general.”

He has found that Dartmouth to be one of the few places where there is “room” to explore one’s faith, especially compared to the other Ivy League schools he has visited.

“The greatest growth I’ve had at Dartmouth has been spiritual,” Ponshunmugam said.

By: Sungil Ahn

In an age when students can find almost any fact in a single Google search, communicate with billions of people across the planet and utilize myriad online learning tools, most courses are still taught in traditional classrooms. Students sit facing forward, listen to a lecturer and jot down notes.

Some classes at the College, however, are starting to look different: students sit in small groups, discuss the lecture material and practice problem solving. The professor and learning fellows walk around the class giving feedback to students. Some professors deliver no lectures at all.

The transformation of classrooms is a direct response to the problems presented by the traditional setup.

Biology professor Thomas Jack noted that students were struggling with problem-solving aspects of Biology 13, “Gene Expression and Inheritance,” which he and his colleagues have taught for decades. Government professor Yusaku Horiuchi realized that some students were afraid of asking questions in big classroom settings. Earth sciences professor Robert Hawley found that in a typical lecture class, only a select few students answered the questions in class.

In order to solve such problems, professors work closely with the Dartmouth Center for the Advancement of Learning, Information Technology Services and technical support staff.

Government and Latin American studies professor Lisa Baldez, the director of DCAL, said that the Center provides resources to improve teaching and learning, transforming Dartmouth classrooms through various initiatives.

One such project, the Gateway Initiative, aims to redesign large introductory courses in order to make them feel more like small classes.

“When you’re in a class, even with 15 students, active learning becomes a challenge — you want to give everyone a chance to participate in learning activity,” said Erin DeSilva, an instructional designer at the College.

Through the initiative, Hawley redesigned his large introductory course — Earth Sciences 6, “Environmental Change” — to incorporate more active learning methods.

In his redesigned course, students are divided up into small groups of seven. Once students receive worksheets from the professor, they discuss the figures in the worksheet and their significance — first with other group members, then with the whole class.

Hawley’s class also involves demonstrations. He asks students to predict what will happen and why. In a demonstration of heat flow, he describes how he plans to put a candle under a measurement device and asks for predictions of how the temperature will rise. Will it be a constant rise or will it rise faster at the beginning or the end? After the experiment, students discuss what they have learned in small groups and then share their consensus with the whole class.

“Typically, in a giant lecture class like this, you have the same four students answering all the questions in the class,” Hawley said. “In this redesigned course, the level of engagement is much higher.”

In other cases, technology has transformed teaching and learning. In her Engineering 20 course, Thayer School of Engineering professor Petra Bonfert-Taylor uses an online coding environment to practice coding in class. It allows students to type code directly in the environment, testing the code out by simply clicking “run” without needing to save or compile first.

“I wanted for students to be able to very quickly try something out,“ she said.

She also utilizes the online platform Piazza as a class forum, where she and her students can discuss issues from homework help to test preparation. Using the platform allows students to get responses faster than they would by emailing the professor or waiting for office hours, she said.

Some professors have completely rethought what constitutes a class.

“I don’t do any lectures,” Horiuchi said, describing the flipped classroom approach he uses in his data visualization course. He gives out homework one session before he covers the material and uses videos and readings to explain what students are expected to learn.

Students complete coding practices as homework. When they come to class, they pick up worksheets and simply write code for the entire 110-minute session.

“I really think this is the better approach,” he said. “I can walk around, I speak to each student, I can see whether the student is having trouble and I can give them feedback.”

While classes like data visualization are suitable for active learning, Horiuchi says the challenge is to introduce these new methods of teaching in “standard” courses.

Jack’s “Gene Expression and Inheritance” is one such example. The introductory biology class deals with conceptual, information-dense material, making student engagement especially crucial for learning, Jack noted. With this in mind, Jack and other biology professors recently transformed the class, which had for decades been a straightforward lecture. Today, students watch prerecorded lecture videos before class. They then spend most of class solving problems in groups.

Other methods to improve learning involve the setup of the physical classroom.

For Horiuchi, the classroom contributes greatly to improving students’ learning experience.

“Carson 61 is effective in active and experiential learning,” he said.

Because the tables are modularized, students can sit anywhere and discuss, whereas in a standard lecture setting, he can’t move around and help students. In addition, each table has a screen that he can use to interact with students and help them with coding practice.

Jack also found his classroom — Life Sciences Center 200 — to be helpful in active learning. LSC 200 has a flat floor with moveable chairs and tables. Because of this arrangement, Jack noted, the whole class feels that they can ask questions — not just the people in the first two rows.

Hawley, who teaches in Cook Auditorium, a traditional lecture hall, finds the room a difficult space to incorporate active learning due to its physical limitations.

The layout inhibits group work because students need to turn around to talk to each other during discussions. Moreover, the long rows of tiered seating make it difficult for the professor and his learning fellows to help groups in the middle of the room.

Baldez said DCAL is just beginning to collect the data on its initiatives’ impact on learning. Due to the length of the data-gathering process and the small size of Dartmouth classes, DCAL has yet to obtain statistically significant results, she explained.

DeSilva added that it is difficult to measure the success of a teaching experience.

“While [the] course assessment report is a really important tool, we have found that it’s a tricky tool,” she said. While students tend to give feedback if they feel strongly about the course, students without a strong reaction tend not to give as much written feedback.

However, some faculty members have begun conducting course evaluations of their own in the middle of the term. These surveys allow faculty to receive student feedback while they are still able to change aspects of the course. Generally, the intermediate evaluations have been very positive, DeSilva said.

Hawley said that students are more engaged in Earth Sciences 6 and that the scores for the first midterm were higher than usual.

“Whether this class is just smarter than the rest, it’s hard to say,” he said.

For Bonfert-Taylor, her online lectures — one of her main methods of improving learning — have been very effective as they help students review material and learn at their own pace instead of a “one-speed-for-all” class, she said.

Baldez noted that active learning improves student knowledge. In addition, students in such classes are more likely to continue taking classes in that course’s major. This benefit is proportionally greater for students from underrepresented minority groups and first-generation college students, she said.

If the introduction of new learning methods is so effective, why has the College started to implement these initiatives in just the past few years?

According to Baldez, the advent of online learning in recent years has pressured the College to articulate its place as a premier liberal arts institution.

“You could take a Harvard computer science course online for free, basically getting the same class that students at Harvard are paying to get,” Baldez said. “So in a digital world like that, what does a Dartmouth education have to offer?”

Recent cognitive, educational and psychological research has provided another impetus for redesigned learning, which pushed faculty to focus more on learning and less on teaching, she said.

While various professors have been able to implement new learning and teaching methods with the help of DCAL and instructional designers like DeSilva, there have been a few difficulties.

Making these changes involve many time-consuming processes, DeSilva noted, such as outlining goals for the class and redesigning course material.

The other big hurdle is sub-optimal classroom design.

“It’s very hard for introductory class of 150 students sitting in a lecture hall to break into groups,” DeSilva said. “We know that’s the best thing for them to learn the content, but they’re still stuck in that room.”

Several classrooms have been redesigned to address the issue, including Carson 61, Silsby 218 and LSC 200.

And while the introduction of active learning into a course can increase the time needed to teach course material, Jack said this wasn’t a problem with “Gene Expression and Inheritance.”

“We still have all the key things in the course,” he said. “The students like it better and the professors like it better too. It’s a win-win.”

By: The Dartmouth Editorial Board

At any school, Homecoming is almost synonymous with tradition: alumni return to campus, myriad events ooze school spirit and everyone goes out to watch the football team play. At Dartmouth, where we often define ourselves by our traditions, this notion is ratcheted up even more. Almost every event during Homecoming weekend, from the bonfire to the alumni parade to Pop Punk, is heavily steeped in Dartmouth tradition. As alumni pour into Hanover and we practice our best “worst class ever!” screams, Homecoming seems to be a good time to contemplate some of the traditions and rituals that permeate student life here at Dartmouth. Why exactly do we do what we do, and are the reasons behind the tradition separate from the tradition itself?

People generally don’t do anything if it doesn’t serve a specific purpose, however large or small that purpose may be. This may seem counterintuitive, considering some of the weirder rituals and practices that some of us may have. What possible purpose could going out of your way to only use a specific “lucky pen” for all of your exams serve? How could counting every single stair in a staircase as we go down it possibly be of use to anyone? The answer, of course, is that these seemingly useless rituals have some kind of psychological utility. A lucky exam pen may help someone feel like they have a little bit more control over the exam they’re about to take. Counting stairs may help keep someone’s mind engaged during what would otherwise be dead time.

The point is, every little thing we do has a specific reason behind it. This begs the question: what are the reasons behind our traditions and rituals? What, specifically, do we get out of them? This is not a question of whether or not the concepts of traditions and rituals themselves are useful. Rather, it’s a question of examining the specific traditions and rituals that we practice here at Dartmouth, and what we do and don’t get out of them.

Some of our most sacred Dartmouth practices are older than any of us, or even our parents. Dartmouth Night has been happening since 1895, and pong dates back to the 1950s. These two rituals will undoubtedly be practiced en masse this weekend, but why is that? The knee-jerk answer may be what is often used to justify a wide range of ritualistic practices: “That’s just how we’ve always done it.” Of course, however, this isn’t enough to justify a ritual’s existence. If we stuck to this logic alone, Dartmouth would never have admitted women, or abandoned its racially insensitive mascot.

Why else do we do engage with these traditions and rituals then? Dartmouth Night — which is mainly known for the bonfire — has become a rite of passage for first-year students. They run around the bonfire while upperclass students shout, “worst class ever!” as a way of showing first-years that they are now part of the Dartmouth community. Does this actually accomplish this goal, though? Do new students feel more at home when they’re running around a giant fireball with hundreds of — often drunk — strangers yelling at them? Perhaps they do; a lot of people will argue that common suffering brings people together. However, it is important to consider the fact that a ritual like this may make people who don’t exactly fit the bill of a “traditional” Dartmouth student feel antagonized.

While some traditions like Homecoming only happen once a year, some are more commonplace. A case in point is pong. This popular social ritual is typically seen as a way to have fun, get drunk and socialize. It would be naïve to say, however, that this is all that ends up happening when people play pong at Dartmouth. While it can be really fun and competitive, pong is also often a means to reinforce several dangerous power dynamics. First off, men control most of the spaces where pong is regularly played; although many local sororities are beginning to establish their own pong scenes, it is safe to say that most people think of it as a game that’s played in fraternity basements. Since men, specifically affiliated men, control most of the spaces where it’s played, you either have to be one or go through one if you want to participate in this historic Dartmouth tradition. This gives affiliated men a lot of power over nearly everyone else and often leads to situations in which asking to play pong is mistaken for an invitation to make unwanted advances.

This is by no means whatsoever a call to abolish the annual Homecoming bonfire, pong or any other Dartmouth tradition. Instead, this is a plea to consider the reasoning behind and usefulness of all of the rituals that we engage in on a daily, weekly or yearly basis. Too often we dive headfirst into these traditions because we just assume that is what a Dartmouth student is supposed to do. Instead, we should think carefully about what each one means before we engage in it. “That’s just how we’ve always done it” is not a good enough reason.

The Editorial Board consists of the editorial chair, the opinion editors and the opinion staff.

By: Matt Yuen

Every year, the seniors of the rubgy team run one practice in prom dresses.

How many times have you done something dumb just for the heck of it? Chances are, probably a lot. You do dumb things, I do dumb things and athletes — yes they are human too — do dumb things. Doing dumb things is an integral component of the human condition. But label these dumb things a tradition, and you’ve got yourself a sports team. Over the past few weeks, I have searched high and low for the most absurd traditions and rituals of Dartmouth athletic teams. What I discovered is that many athletes are unwilling to disclose their clandestine practices. But with my unparalleled persuasion and charm, I was able to unearth some of their most hidden practices, and I have to say — keeping these traditions a secret is definitely a wise move. However, there were some traditions I deemed marginally appropriate for the public eye — traditions which often carry powerful significance and sentiments.

The football team’s most prominent and perhaps least sanitary tradition revolves around the large “D” painted on their locker-room floor. For the football players, the “D” in the locker-room is sacred. If anyone steps on it by accident, they have to plop down on the floor and kiss it. And because each freshman class is unequivocally the worst class ever, it is mostly the freshmen that fall prey to this tradition.

The football guys do have some more serious practice. After each game, they sing the alma mater together. They also sing “As the Backs Go Tearing By” in the locker room and count off how many points they scored. Unlike the less serious “D” tradition, the songs pay homage to the sport, the fans, the Dartmouth community and to the brotherhood within the football team.

“It creates this team unity when everyone is fired up, putting your arms around each other and singing the song enthusiastically,” said Drew Hunnicutt ’19, a wide receiver on the team. “Everyone becomes closer, and it definitely represents the brotherhood on the team.”

The ultimate frisbee team also sings a cheer at every one of their games. But even if you stood directly next to the team, you might not catch all the words.

“[The cheer] is really loud and chaotic,” Johnny Elliott ’19 said. “Because not everyone knows the words, there’s a lot of shouting so that other people can’t really hear the words if you were listening.”

Only at the end-of-the-year banquet do the upperclassmen teach the words of the cheer to the freshmen. Elliot noted that learning the words made him feel closer to the community.

Many ultimate players, however, forget the cheer in the offseason. Instead of singing, they shout gibberish to cover up the actual words.

On the surface, it seems like this tradition epitomizes nonsense. And to some extent, a bunch of crazed ultimate players yelling at the top of their lungs is nonsensical. Yet at the core of this goofy tradition is a beautiful and powerful story of one of the early members of the ultimate community.

According to Elliott, the cheer contains complex themes and motifs that not even he understands completely. It is based on a student who played ultimate for Dartmouth back in the day — whenever that was. The player was diagnosed with cancer, and he passed away shortly after. At every single ultimate game, his legacy is carried on through the cheer.

“I think it’s definitely one of the biggest emotional ties within the frisbee community,” Elliott said. “Because it’s a legacy or ritual that is always within the program since whenever it started.”

These traditions are getting a bit too sentimental. Let’s turn to women’s rugby, whose traditions are some of the most egregious.

At one practice a year, the seniors take a trip down memory lane, all the way back to high school. Picture a squad of strong, athletic women tackling each other to the dirt. Now imagine them wearing prom dresses.

“All the seniors would be out there throwing rugby balls while in their dresses, and it’s really funny since a lot of the girls on the team are tomboyish and athletic,” co-captain Ashley Zepeda ’18 said. “So when you see them running around in the dresses it’s really weird but it’s hilarious.”

Unsurprisingly, the women’s rugby team also has a fair number of singing traditions. At the beginning of each game, the women sing a song written by the original team. It tells the extravagant tale of a ’79 in Heorot who started coaching a group of women to play rugby. Each day, they would traipse all the way off campus, down Main Street, across Mink Brook and down to Sachem Field. That’s dedication. The song goes on to describe how the women’s team rolled to a 3-0 record that first season.

The song is a relic as old as the program itself. It’s a pregame pause to reconnect with the team’s original roots, a reminder to the players that the legacy of rugby continues to live on through them.

The team also sings “rugby songs,” which are prevalent in rugby teams across the country and the world. I can’t describe them in detail — a Google search for some of the lyrics will demonstrate why. These songs also serve to connect current and past Dartmouth women’s rugby players.

The rugby songs also cross collegiate barriers. Zepeda noted that at a game last year the team sang songs after the game with the opposing team. She said it was cool to share traditions with another team.

“They didn’t know some of ours, and we didn’t know some of theirs. So we taught each other the songs, and kind of went back and forth,” she said.

My exploration of sports teams traditions suggest we shouldn’t dismiss them as just goofy behavior. They weave teams together as tightly knit communities. They remind the players of their team’s historical roots. They carry on legacies of the players before current players’ time. They remind players to always watch their step in the locker room. Most importantly, they add life and meaning that make the sport more than just a sport.

“I think traditions of rugby have made it more than just a sport for me — it’s a community,” Zepeda said. “So instead of just looking forward to practice, I can look forward to all the memories the traditions will make.”

By: Natalie Mendolia

Natalie and her father stand on the beach.

As the particles of ink amalgamated on my skin, I felt adrenaline course through my veins. Minute by minute, the tattoo’s permanence creased itself across my tanned skin. Its delicate scratches formed the Roman numeral for 18. As I bit my tongue in a rewarding kind of pain, nostalgia and pride entwined with a question that I had only just begun answering: “I made it, didn’t I?”

Seven months before I reclined on Brooklyn Tattoo’s trendy leather table, I sat in a Dick’s House counseling office across from a stranger. Sobs shook my body while my face tried yet failed to remain stoic. That January resides in my memory as a museum of the emotional aftermath I faced after losing my father on Christmas Day the month before. Chronically ill since birth, my father stood as a pillar of wisdom, love and strength that I strive to emulate. And so, even though my family and I had preemptively grieved long before his passing, his death was striking — a bolt of lightning in the storm of freshman fall.

My dad, uncle and grandmother made up my eclectic parenting crew. They raised my older sister and me to courageously watch those daunting kinds of lightning strikes and find a way to use their light for something good — to persevere no matter what. But as a unit, we faced more sickness — from AIDS to PTSD to congenital heart malfunction — and more money issues than anyone would have liked in our small, lower-middle class Italian neighborhood in Brooklyn. And so, those lightning strikes became ways to cover our pain, just like when I tried to return to campus a week after the funeral and continue as if my life had not just unequivocally altered its path. Pushing things under the rug can momentarily help you move forward, but it eventually fails. For as much as I wanted to pick up and carry on, I couldn’t.

Seven months before I chose my first tattoo, I took a medical leave from Dartmouth, a place whose acceptance letter had brought ardent pride to my family. But on that fateful day in January, I watched the campus spin in circles around my grief-stricken head. The cold didn’t just hang on the leafless trees. It froze in my lungs and made the simplest tasks — brushing my teeth, changing my clothes — incomprehensibly difficult.

What is the point of being here when he isn’t? The words spun through my mind in a frenetic repetition as I tried to focus on the logistics of leaving: filing paperwork, cleaning out my room, contacting my family.

Many members of our community do not know how straightforward it can be to take a medical leave. Within two days of asking for advice from a counselor on campus, the administration, namely Counseling and Human Development and the Deans Office, completed my leave paperwork. Within two more, I was sitting on my couch with take-out and a fuzzy blanket.